Posted: June 1, 2009

Date of Sighting: 31st. May '09

Time: 00:30 a.m. approx.

Witness Statement: Huge ball of bright

orange light traveling at speed from North to West. There was no sound.

Same height as plane would be, but faster than plane. I thought it must

be an aircraft on fire, perhaps being hijacked and I was waiting to

hear a crash as it landed, but heard nothing. I thought then it must be

a meteor or something.

Can't see it being chinese lanterns. Too high up, too fast and powerful, too big.

UK UFO Sightings

Mon, 01 Jun 2009 15:48 UTC

Posted: June 1, 2009

Date of Sighting: 30th May 2009

Time: 10:50pm

Witness Statement: I saw the anomaly,

much like a flaming orange ball traveling North to South initially, at

an estimated 5-10,000 ft. It was traveling about 2 or 3 times faster

than a plane with no noise, I thought it was an asteroid initially.

However, it seemed to slow down and then travel in a West direction

rapidly increasing in speed and altitude, traveling roughly 5 times the

speed of a plane. The whole experience lasted about 1m 30 secs. Both my

partner and I witnessed it and have never seen anything like it before.

Brian Vike

HBCC UFO Research

Tue, 02 Jun 2009 13:21 UTC

Posted: June 2, 2009

Date: May 28, 2009

Time Approx: 11:30 p.m.

Number of witnesses: 2

Number of Objects: 1

Shape of Objects: Orb-like.

Full Description of Event/Sighting:

Driving down highway 12 slowing down for construction, I had seen a

medium-sized green fireball-like orb falling towards the ground at a

close 45 degree angle approximately 1 mile away. I wasn't sure if it

were fireworks or a flare gun initially considering the construction

nearby. I also had considered a falling star. A couple of seconds later

I realized it couldn't have been either of those and quickly asked my

girlfriend sitting next to me what it could be. We both looked at it

for 3-4 seconds as it rapidly fell towards the ground. We weren't able

to see where it fell due to a blocking view caused by a big-rig truck.

We're not exactly sure if anyone else had seen the

green fireball as well since there were so many distractions and nobody

stopped in their tracks to look in awe.

UK UFO Sightings

Thu, 04 Jun 2009 14:41 UTC

Posted: June 4, 2009

Date of Sighting: 31st May 2009

Time: 10-11 PM

Witness Statement: I was having a ciggie

out of the bathroom window and saw a large 'fireball' (glowing orange)

moving horizontally and quite low in the sky. This thing appeared to be

both bigger than a 747, and faster than any plane or helicopter. I

watched it, shouted and ran to get my partner, was literally gone 3-4

seconds, and when I returned it had just vanished ! Impossible! I know

what I saw, and it wasn't anything man made (that I know of !). Just a

big ball of 'fire' flying at a constant speed and height.

It's stayed in my mind all day as it was so bizarre. This definitely wasn't a meteor so what was it ?

Abhinav Malhotra

The Times of India

Wed, 03 Jun 2009 18:15 UTC

"Meteorite is a rocky material which enters into earth's atmosphere

from outside the earth (for eg, Mars) whereas numerous small and big

rocks circulating in between the planets Mars and Jupiter are known as

asteroids," said Prof Harish Chandra Verma of department of Physics of

IIT-K while talking to TOI, specifying the difference between a

meteorite and an asteroid.

Prof Verma ruled out the possibility of the stone being an

asteroid as reported in some newspapers and emphatically remarked that

the initial study of the piece of the rock done on Wednesday confirms

that it's a meteorite. Usually such pieces of rock (debris) come from

asteroid belt only but sometimes they may very well be a part of other

celestial bodies also.

Prof Verma was referring to the incident

of May 28, when a 1 kg stone resembling a meteorite fell down from the

sky about 12 noon and left the people of the Karimatti hamlet

in Hamirpur district amazed and puzzled. The stone which is ten inches

in length and five inches in width was put in water to bring down its

high temperature. Eyewitness to the entire incident, Mannu Lal, a

villager was the first to observe this heavenly body. In no time, the

news of the incident had spread like a wild fire in the entire village.

The matter was then referred to the administration, which took the

stone in its possession.

Prof Verma, travelled 200 km and brought the stone to IIT-K on

Tuesday last for detailed study. Visibly excited with the discovery of

the magnetic stone, Prof Verma shared his experience and said, "It's

confirmed now that it is a meteorite due to its properties. As it was

getting attracted towards a magnet and also the whole of the stone was

covered with a black layer it gave us an idea of it being a

meteorite.''

"Genuine scientific tests done on this meteorite will help us

to know more about the secrets of the solar system like what was the

composition of the solar system when it was formed, what was the early

solar system like etc," he further said.

Prof Verma went on to say that the researchers from Physical

Research Lab, Ahmedabad, University of Jodhpur, Bhaba Atomic Research

Centre (BARC) and IIT-K will carry out tests in collaboration.

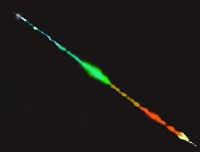

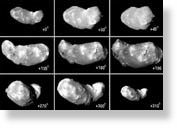

The

asteroid 951 Gaspra, the first ever imaged by a spacecraft, taken by

Galileo as it passed by it in 1991; the colors are exaggerated.

Swiss

astronomer Jose De Queiroz on Wednesday announced the discovery of two

new asteroids between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

According to the Mirasteilas Observatory, De Queiroz has located two new asteroids with a diameter of between 1 kilometer and 2 kilometers.

According to the Associated Press, the discovery of 2009FM1 and

2009FA1 was confirmed by the Minor Planet Center of the International

Astronomical Union in Cambridge, Massachusetts in March.

"They're perfectly ordinary objects and intrinsically very faint," said Bryan Marsden, of the Minor Planet Center.

Marsden added that De Queiroz would have to continue to observe the two

new asteroids for the next four years in order to confirm their

existence.

"They've only been observed this year," he said.

The newly discovered asteroids are just two out of hundreds of

thousands currently falling between the two planets. Marsden said many

of the asteroids around the main belt have been documented, but amateur

astronomers like De Queiroz continue to find new ones.

De Queiroz hopes to name the asteroids 'Falera,' after the site of his observatory, and 'Marcia,' after his daughter.

"If the observations are just over the course of a month or

two, that's not enough for us to accept the names that he's proposing,"

said Marsden.

This

image shows the area of sky around the Arietid radiant (indicated by a

red dot) as seen from mid-northern latitudes at 4 a.m. on June 7th or

8th.

The annual Arietid meteor shower peaks this

weekend on Sunday, June 7th. The Arietids are unusual because they are

daytime meteors; the shower is most intense after sunrise. Early risers

could spot a small number of earthgrazing Arietids during the dark

hours before dawn on Sunday morning.

Every year in early June, hundreds of meteors streak across the sky.

Most are invisible, though, because the sun is above the horizon while

the shower is most intense. These daylight meteors are called the

Arietids. They stream from a radiant point in the constellation Aries,

which lies just 30 degrees from the Sun in June.

Arietid meteoroids hit Earth's atmosphere with a velocity of

39 km/s (87,000 mph). No one is sure where these meteoroids come from.

Possibilities include sungrazing asteroid 1566 Icarus, Comet

96P/Machholz, and the Kreutz family of sungrazing comets. The debris

stream is quite broad: Earth is inside it from late May until early

July. In most years, the shower peaks on June 7th or 8th.

If you want to see a few Arietids, try looking just

before sunrise. The Arietid radiant rises in the east about 45 minutes

before the sun. (This is true for observers in both of Earth's

hemispheres, north and south.) Pre-dawn Arietids tend to be

"Earthgrazers"--meteors that skim horizontally through the upper

atmosphere from radiants near the horizon. Spectacular Earthgrazers are

usually slow and bright, streaking far across the sky--worth waking up

for!

After daybreak, you can listen to the shower by tuning into our online meteor radar.

Dhenkanal, India: Mr Anil Hota of Ichchbatipur, under Baruna gram

panchayat, in Kamakshanagar subdivision, was carrying a palm leaf sheet

over his head, while moving around in the village today.

Scorching heat, is not the only reason for such protective

measures adopted by Mr Anil and other villagers, as all of them resort

to leaf sheets or umbrellas, at the dead of the night, these days too.

Much to the disbelief of the outsiders, the villagers of Ichchbatipur

claim that, for last few days they have been witnessing bizarre and

mysterious incidents like dropping of stone pieces and splinters from

above and other directions.

Hence, it was no surprise that at the Pandua outpost and

Kamakshanagar police station police officers, were taken aback

yesterday when the villagers came in large numbers and narrated the

"disturbance" in the village, which is taking place from Saturday

night, while requesting them to take "necessary action". The police,

however, were helpless too and could do nothing except visiting the

village and starting an inquiry.

Saturday night was as like any other night for Mr

Hemant Mohapatra. But at about 12, his slumber was disturbed by a

strange sound. He woke up and realized that stone pieces were falling

on his roof. Though, he immediately could not figure out what exactly

had happened or who was doing it, he saw similar "attack" on the

verandah and roof of many neighbours. They too could not understand

what was happening and with utter disbelief, fear and confusion, all

started searching for any clue, but in vain.

Mr Srikant Hota, a fellow villager informed the curious and

confused neighbours that one big stone had fallen from above injuring

him. He showed the injuries marks on his body.

As the news spread in the morning, thousands of people from

nearby areas rushed to the village. Though the whole incident is still

wrapped in mystery, the villagers preferred to remain indoors.

"We searched extensively for the origin of the stones, but

found no answer for the mystery," said Mr Hemant Mohapatra, who has

sustained injuries.

Many villagers feel that it is a supernatural phenomenon, while

some maintain that this was the handwork of a sorcerer. Kamakshanagar

MLA, Mr Prafulla Mallick, visited the village and discussed with the

residents yesterday.

Meanwhile, the villagers are getting ready to offer mass

prayer before Lord Hanuman, seeking divine intervention to ward off the

evil power.

Robert Roy Britt

Space

Wed, 16 Jul 2003 18:39 UTC

When

asteroids fall through Earth's atmosphere, a variety of things can

happen. Large iron-heavy space rocks are almost sure to slam into the

planet. Their stony cousins, however, can't take the pressure and are

more likely to explode above the surface.

Either outcome can be dismal. But the consequences vary.

So scientists who study the potential threat of asteroids would

like to know more about which types and sizes of asteroids break apart

and which hold together. A new computer model helps to quantify whether

an asteroid composed mostly of stone will survive to create a crater or

not.

A stony space rock must be about the size of two football

fields, or 720 feet (220 meters) in diameter, to endure the thickening

atmosphere and slam into the planet, according to the study, led by

Philip Bland of the Department of Earth Science and Engineering at

Imperial College London.

"Stones of that size are just at the border where they're

going to reach the surface -- a bit lower density and strength and

it'll be a low-level air burst, a bit higher and it'll hit as a load of

fragments and you'll get a crater," said Bland, who is also a Royal

Society Research Fellow.

The distinction would mean little to a person on the ground.

Two ways to destroy a city

"An airburst would be a blast somewhere in the region of 500-600

megatons," Bland said in an e-mail interview. "As a comparison, the

biggest-ever nuclear test was about 50 megatons."

A presumed airburst in 1908,

over a remote region of Siberia called Tunguska, flattened some 800

square miles (2,000 square kilometers) of forest. The object is

estimated to have been just 260 feet wide (80 meters). Bland said the

event was probably equal to about 10 megatons.

"If most of it made it to the ground you might actually be a

bit better off, because the damage would be a little more localized,"

he said. "A lot of energy would still get dumped in the atmosphere, but

you'd probably also have a ragged crater, or crater field, extending

over several kilometers, with the surrounding region flattened by the

blast."

Smaller stony asteroids, say those the size of the car, enter

the atmosphere more frequently but typically disintegrate higher up and

cause no damage. In fact, as many as two or three dozen objects ranging

from the size of a television to a studio apartment explode in the atmosphere every year, according to data from U.S. military satellites.

Separate research in recent years has shown that stony asteroids are

often mere rubble piles, somewhat loose agglomerations of material that

may have been shattered in previous collisions but remain

gravitationally bound.

Pieces and parts

The new computer model is detailed in the July 17 issue of the journal Nature. It was created with the help of Natalia Artemieva at the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Previous models treated the cascade of fragments from a

disintegrating asteroid as a continuous liquid "pancake." The new model

tracks individual forces acting on each fragment as the bunch descends.

The researchers can plug in asteroid size, density, strength,

speed and entry angle at the top of the atmosphere. With "reasonable

confidence" a computer program then details how that rock should behave

in the air and what will happen at the surface.

The model has implication not just for land-based impacts, but

also splashdowns in the ocean that can trigger devastating tsunamis. An

airburst is not likely to generate much of a tsunami, possibly lowering

that risk compared to what scientists had figured.

The results suggest rocks about 720 feet across (220 meters)

are likely to actually hit the surface every 170,000 years or so. Some

previous research has suggested a frequency of every 4,000 years or

less.

Looking back

The model can also "hindcast" what sort of rock might have generated a certain known crater.

"You see a crater field on Mars, we can tell you what sort of object caused it," Bland said.

In fact, he and Artemieva have done just that. In their most recent tests, which are not discussed in the Nature

paper, they plugged in the atmospheric details of Mars, as well as

Venus, and hurled some hypothetical space rocks at those planets.

"The simulated crater fields that the model produces look almost exactly like the real thing," Bland said.

For now, the model does not handle very large asteroids, those

that could cause widespread regional or even global damage, though

Bland said the flaw may be fixable. He is careful to point out that

computer models do not provide solid proof for what might happen.

"There are still a lot of unknowns in this," he said.

Flashback:

When Meteors Explode: Full Account of a Wild Chicago Night

Space

Mon, 19 Apr 2004 18:07 UTC

Robert Roy Britt

You might think meteor expert Steven Simon knew exactly what was

happening one evening when the skies over his home were lit up by an

exploding, 2,000-pound space rock bigger than a refrigerator. But it

was only the next day, when nearby residents brought him chunks of the

extraterrestrial visitor that had landed in the street and punched

through their roofs, that Simon began to understand the true nature of the frightening event.

Now after a year of study, the University of Chicago researcher has

helped produce a full account of the giant rock that tore through the

atmosphere at 54 times the speed of sound.

Simon was in his Park Forest home about 30 miles south of Chicago with the drapes drawn near midnight on March 26, 2003.

"I saw the flash, and although it lasted longer than a

lightning flash, that's what I thought it was," he told SPACE.com last

week. "I knew it had rained that night, and thought maybe it was

multiple flashes, perhaps diffused by the clouds."

Lawrence Grossman, a geophysicist who oversees Simon's

research, got a different impression of the incoming object from his

home in nearby Flossmoor.

"I heard a detonation," Grossman said the morning after the event. "It was sharp enough to wake me up."

The fireball in the sky was witnessed across a wide area, from

Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Missouri. Simon and Grossman teamed up

with other researchers to gather rocks and eyewitness accounts and then

calculate the space rock's original size, composition and origin, and

to trace its fragmented path from space to Earth. Their findings are

detailed in the April issue of the journal Meteoritics and Planetary Science.

Daily barrage

Several tons of space stuff rain down on the planet every day. Much of

it is dust. Objects no larger than sand grains generate typical

"shooting stars" when they vaporize.

Playing marble-sized objects can create dramatic fireballs

that prompt phone calls to local law enforcement. Asteroids bigger than

about 100 feet (30 meters) can mostly survive the plunge, possibly

hitting the surface or exploding devastatingly close to the ground. The

latter events are very rare.

Scientists call all these things meteors once they enter the

atmosphere. When in space, the same objects might be referred to as

asteroids if they are large, or meteoroids if they are small. If they

hit the ground, they're called meteorites.

Whether the things vaporize, break apart or reach the surface

intact depends in part on whether they are made mostly of fragile stone

or of more durable iron.

The Chicago rock was stony and about 6 feet in diameter, the researchers conclude.

About 10 objects of this size enter the atmosphere every year,

according Doug ReVelle of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which

uses satellites and other means to monitor the resulting explosions and

separate them from possible rogue-nation nuclear detonations.

Most of these in-air explosions are not noticed by eyewitnesses because

so much of the world, including the two-thirds that is water, is

unpopulated.

Chicago fireball

Here's what happened over Chicago:

"It hit the atmosphere at about 40,000 mph," Simon said. "At

this great speed, air pressure builds up in front of the object and is

much greater than the pressure behind it. This will pull apart many

meteors, especially if they already had some cracks. This object

probably went though four fragmentation events as it passed through the

atmosphere."

Tremendous heat created by the pressure lit much of the object in a fiery display.

Park Forest resident Noe Garza was asleep when a fragment burst

through his ceiling, sliced some window blinds, then bounced across the

room and broke a mirror. "I thought somebody was breaking in," Garza

told a new agency the next day. "It was a big bang. I can't really

describe it."

Another resident whose home was hit said the room lit up and it sounded like a plane had crashed.

Simon's team examined hundreds of fragments -- 65 pounds worth

that were picked up and delivered to the scientists -- to estimate the

original rock's size and weight.

The measurements are difficult to pin down, he explained,

because a lot of fragments probably hit wooded areas and were not

found. And some of the original meteor was probably broken into

particles too small to notice. The scientists also analyzed the

fragments for a certain radioactive form of cobalt, which can reveal

the rock's minimum size. "If the object is too small [while in space

for eons] the cosmic rays will just pass through and not make 60

cobalt," Simon said.

He said the original rock weighed at least 1,980 pounds as it

entered the atmosphere. Long ago, the analysis shows, it was probably

heated for a long period of time inside a larger parent asteroid. That

asteroid then broke apart, again a long time ago, perhaps in a

collision with another asteroid.

The researchers found in the fragments a mineral called

shocked feldspar, which suggests the ancient collision between two

asteroids.

There are no records of a meteorite ever killing anyone. But there have been injuries. A dog was killed by a space rock in Egypt in 1911.

The Park Forest meteorite event is not totally unlike others

that have been reported in recent years. A similar meteorite shower rattled a village in India last September, apparently injuring three people. Other reports of fireballs in the sky are fairly common, and the occasional small rock slices through a home.

But Simon and his colleagues write in their report of an important

distinction with the Chicago event: "This is the most densely populated

region to be hit by a meteorite shower in modern times."

Flashback:

Exploding Asteroids; Satellites Monitor Threat to Earth

Robert Roy Britt

SPACE.com

Wed, 20 Nov 2002 18:19 UTC

Researchers have determined, with the assistance of US military

satellites, that the risk of Earth being struck by a killer asteroid is

less likely than previously believed.

If you've ever gazed up and spotted a shooting star, you engaged in a

form of astronomy in which Earths atmosphere serves as a giant

detector: Space debris screams through the air, which heats the stuff

up and makes it visible.

By noting observations night after night, you could develop a

record of how frequently certain sized objects most no larger than a

pea meet their demise by running into our planet.

But if you want to know how often larger hunks of cosmic

rubble arrive, your job is far more difficult. It could take hundreds

or even thousands of years of continuous observations to arrive at a

reliable estimate.

The prospect was not an option for Peter Brown of the

University of Western Ontario. So he and some colleagues turned to a

higher-tech version of the same method, and then applied some fancy

extrapolations. The researchers studied observations by U.S. government

satellite sentinels that watch for potential nuclear detonations around

the globe, 24/7.

More than eight years of data reveal 300 in-air explosions of

space rocks ranging in size from large televisions to studio

apartments.

Objects in this size range rarely reach the ground.

They disintegrate catastrophically but high up. While some of their

shards can hit the planet the burned remains of space debris add tons

of heft to Earth every day, astronomers say the damage potential is

limited.

"There will often be a shower of small stony objects," Brown

explained. "But theres essentially no significant amount of energy

thats imparted to the ground."

Because most of these events occur over remote regions or

oceans (Earth is about two-thirds water) the majority of them go

unnoticed except by satellites operated by the Department of Defense

and the Department of Energy. Brown and his colleagues used the power

output of the explosions to estimate how big each rock was.

The researchers were interested in larger objects, however,

those roughly as big as a football field that strike even less often

but can get real nasty down here on the ground. These large boulders

typically explode, too, but they do so closer to the surface. A shock

wave could kill millions of people if one exploded over a populated

area.

The last known event like this was in 1908, over the remote

Tunguska region of Siberia. Mostly uninhabited forest was flattened for

hundreds of miles in every direction.

Until recently, experts thought events like this might occur

once per century. A perception had developed in some minds that Earth

was due for another mini-cataclysm.

When Brown extrapolated his data on relatively small rocks

upward to estimate Tunguska event frequency, he found they probably

occur every 1,000 years or so. The results will be reported in

tomorrows issue of the journal Nature.

He notes, however, that because his team had less than a

decade of data to work with, its possible the actual rate of events is

higher than observed. Other researchers have speculated that swarms or

streams of asteroids might generate flurries of impacts now and then.

No such events have been recorded in modern times. However, ancient tales and drawings hint at the possibility.

The new analysis dovetails with another recent study

that approached the question from the opposite direction. Alan Harris

of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, CO used actual tallies of

Tunguska-sized rocks discovered out in space to estimate the quantity

of smaller rocks that probably exist. He, too, found that Tunguska

events ought to occur only about once every 1,000 years.

"We can all worry a little less about the risk of the next

hazardous impact," said Robert Jedicke, a University of Arizona

researcher who was not involved in the new study but wrote an analysis

of it for Nature.

However, unlike the recent Leonid meteor shower,

which was well predicted, scientists dont yet have enough data on the

populations of large meteoroids and asteroids to say when the next one

is coming. They caution that statistics and odds cannot be converted to

precise timetables. A giant asteroid might explode disastrously above

San Francisco tomorrow, or none might arrive on the entire planet for

millennia.

Nature does not deliver doom on any scientists schedule.

Comment: This article was written in 2002, obviously things have changed celestially since those days.....and changed legally too: Military Hush-Up: Incoming Space Rocks Now Classified

Andrea Thompson

SPACE.com

Wed, 25 Mar 2009 18:45 UTC

Meteorite fragments of the first asteroid ever spotted in space before

it slammed into Earth's atmosphere last year were recovered by

scientists from the deserts of Sudan.

These precious pieces of space rock, described in a study detailed in the March 26 issue of the journal Nature, could be an important key to classifying meteorites and asteroids and determining exactly how they formed.

The asteroid was detected by the automated Catalina Sky Survey

telescope at Mount Lemmon , Ariz., on Oct. 6, 2008. Just 19 hours after

it was spotted, it collided with Earth's atmosphere and exploded 23 miles (37 kilometers) above the Nubian Desert of northern Sudan.

Because it exploded so high over Earth's surface, no chunks of it were

expected to have made it to the ground. Witnesses in Sudan described

seeing a fireball, which ended abruptly.

But Peter Jenniskens, a meteor astronomer with the SETI

Institute's Carl Sagan Center, thought it would be possible to find

some fragments of the bolide. Along with Muawia Shaddad of the

University of Khartoum and students and staff, Jenniskens followed the

asteroid's approach trajectory and found 47 meteorites strewn across an

18-mile (29-km) stretch of the Nubian Desert.

"This was an extraordinary opportunity, for the first

time, to bring into the lab actual pieces of an asteroid we had seen in

space," Jenniskens said.

Classification

Astronomers were able to detect the sunlight reflected off the car-sized asteroid (much smaller than the one thought to have wiped out the dinosaurs)

while it was still hurtling through space. Looking at the signature of

light, or spectra of space rocks is the only way scientists have had of

dividing asteroids into broad categories based on the limited

information the technique gives on composition.

However, layers of dust stuck to the surfaces of the asteroids

can scatter light in unpredictable ways and may not show what type of

rock lies underneath. This can also make it difficult to match up

asteroids with meteorites found on Earth - that's why this new

discovery comes in so handy.

Both the asteroid, dubbed 2008 TC3, and its meteoric fragments indicate that it could belong to the so-called F-class asteroids.

"F-class asteroids were long a mystery," said SETI planetary

spectroscopist Janice Bishop. "Astronomers have measured their unique

spectral properties with telescopes, but prior to 2008 TC3 there was no

corresponding meteorite class, no rocks we could look at in the lab."

Cooked carbon

The chemical makeup of the meteorite fragments, collectively known as

"Almahata Sitta," shows that they belong to a rare class of meteorites

called ureilites, which may all have come from the same original parent

body. Though what that parent body was, scientists do not know.

"The recovered meteorites were unlike anything in our meteorite collections up to that point," Jenniskens said.

The meteorites are made of very dark, porous material that is

highly fragile (which explains why the bolide exploded so high up in

the atmosphere).

The carbon content of the meteorites shows that at some point in the past, they were subjected to very high temperatures.

"Without a doubt, of all the meteorites that we've ever

studied, the carbon in this one has been cooked to the greatest

extent," said study team member Andrew Steele of the Carnegie

Institution in Washington, D.C. "Very cooked, graphite-like carbon is

the main constituent of the carbon in this meteorite."

Steele also found nanodiamonds in the meteorite, which could

provide clues as to whether heating was caused by impacts to the parent

asteroid or by some other process.

Rosetta Stone

Having spectral and laboratory information on the meteorites

and their parent asteroid will help scientists better identify ureilite

asteroids still circling in space.

"2008 TC3 could serve as a Rosetta Stone, providing us with

essential clues to the processes that built Earth and its planetary

siblings," said study team member Rocco Mancinelli, also of SETI.

One known asteroid with a similar spectrum, the 2.6-km wide

1998 KU2, has already been identified as a possible source for the

smaller asteroid 2008 TC3 that impacted Earth.

With efforts such as the Pan-STARRS project sweeping the skies in search of other near-Earth asteroids, Jenniskens expects that more events like 2008 TC3 will happen.

"I look forward to getting the next call from the next person

to spot one of these," he said. "I would love to travel to the impact

area in time to see the fireball in the sky, study its breakup and

recover the pieces. If it's big enough, we may well find other fragile

materials not yet in our meteorite collections."

Space

Tue, 13 Nov 2001 18:25 UTC

Robert Roy Britt

If you are fortunate enough to see the storm of shooting

"...and the seven judges of hell ... raised their torches, lighting the

land with their livid flame. A stupor of despair went up to heaven when

the god of the storm turned daylight into darkness, when he smashed the

land like a cup."

-- An account of the Deluge from the Epic of Gilgamesh, circa 2200 B.C.

stars predicted for the Nov. 18 peak of the Leonid meteor shower,

you'll be watching a similar but considerably less powerful version of

events which some scientists say brought down the world's first

civilizations.

The root of both: debris from a disintegrating comet.

Biblical stories, apocalyptic visions, ancient art and

scientific data all seem to intersect at around 2350 B.C., when one or

more catastrophic events wiped out several advanced societies in

Europe, Asia and Africa.

Increasingly, some scientists suspect comets and their associated meteor storms were the cause.

History and culture provide clues: Icons and myths surrounding the

alleged cataclysms persist in cults and religions today and even fuel

terrorism.

And a newly found 2-mile-wide crater in Iraq, spotted

serendipitously in a perusal of satellite images, could provide a

smoking gun. The crater's discovery, which was announced in a recent

issue of the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, is a

preliminary finding. Scientists stress that a ground expedition is

needed to determine if the landform was actually carved out by an

impact.

Yet the crater has already added another chapter to an

intriguing overall story that is, at best, loosely bound. Many of the

pages are washed away or buried. But several plot lines converge in

conspicuous ways.

Too many coincidences

Archeological findings show that in the space of a few

centuries, many of the first sophisticated civilizations disappeared.

The Old Kingdom in Egypt fell into ruin. The Akkadian culture of Iraq,

thought to be the world's first empire, collapsed. The settlements of

ancient Israel, gone. Mesopotamia, Earth's original breadbasket, dust.

Around the same time -- a period called the Early Bronze Age

-- apocalyptic writings appeared, fueling religious beliefs that

persist today.

The Epic of Gilgamesh describes the fire, brimstone and flood

of possibly mythical events. Omens predicting the Akkadian collapse

preserve a record that "many stars were falling from the sky." The

"Curse of Akkad," dated to about 2200 B.C., speaks of "flaming

potsherds raining from the sky."

Roughly 2000 years later, the Jewish astronomer Rabbi bar

Nachmani created what could be considered the first impact theory: That

Noah's Flood was triggered by two "stars" that fell from the sky. "When

God decided to bring about the Flood, He took two stars from Khima,

threw them on Earth, and brought about the Flood."

Another thread was woven into the tale when, in 1650, the

Irish Archbishop James Ussher mapped out the chronology of the Bible --

a feat that included stringing together all the "begats" to count

generations -- and put Noah's great flood at 2349 B.C.

All coincidence?

A number of scientists don't think so.

Mounting hard evidence collected from tree rings, soil layers

and even dust that long ago settled to the ocean floor indicates there

were widespread environmental nightmares in the Near East during the

Early Bronze Age: Abrupt cooling of the climate, sudden floods and

surges from the seas, huge earthquakes.

Comet as a culprit

In recent years, the fall of ancient civilizations has come to

be viewed not as a failure of social engineering or political might but

rather the product of climate change and, possibly, heavenly

happenstance. As this new thinking dawned, volcanoes and earthquakes

were blamed at first. More recently, a 300-year drought has been the

likely suspect.

But now more than ever, it appears a comet could be the culprit.

One or more devastating impacts could have rocked the planet, chilled

the air, and created unthinkable tsunamis -- ocean waves hundreds of

feet high. Showers of debris wafting through space -- concentrated

versions of the dust trails that create the Leonids -- would have

blocked the Sun and delivered horrific rains of fire to Earth for

years.

So far, the comet theory lacks firm evidence. Like a crater.

Now, though, there is this depression in Iraq. It was found

accidentally by Sharad Master, a geologist at the University of

Witwatersrand in South Africa, while studying satellite images. Master

says the crater bears the signature shape and look of an impact caused

by a space rock.

The finding has not been developed into a full-fledged

scientific paper, however, nor has it undergone peer review. Scientist

in several fields were excited by the possibility, but they expressed

caution about interpreting the preliminary analysis and said a full

scientific expedition to the site needs to be mounted to determine if

the landforms do in fact represent an impact crater.

Researchers would look for shards of melted sand and telltale

quartz that had been shocked into existence. If it were a comet, the

impact would have occurred on what was once a shallow sea, triggering

massive flooding following the fire generated by the object's partial

vaporization as it screamed through the atmosphere. The comet would

have plunged through the water and dug into the earth below.

If it proves to be an impact crater, there is a good chance it

was dug from the planet less than 6,000 years ago, Master said, because

shifting sediment in the region would have buried anything older.

Arriving at an exact date will be difficult, researchers said.

"It's an exciting crater if it really is of impact origin," said Bill Napier, an astronomer at the Armagh Observatory.

Cultural impact

Napier said an impact that could carve a hole this large would

have packed the energy of several dozen nuclear bombs. The local

effect: utter devastation.

"But the cultural effect would be far greater," Napier said in

an e-mail interview. "The event would surely be incorporated into the

world view of people in the Near East at that time and be handed down

through the generations in the form of celestial myths."

Napier and others have also suggested that the swastika, a

symbol with roots in Asia stretching back to at least 1400 B.C., could

be an artist's rendering of a comet, with jets spewing material outward

as the head of the comet points earthward.

But could a single impact of this size take down civilizations on three continents? No way, most experts say.

Napier thinks multiple impacts, and possibly a rain of other

smaller meteors and dust, would have been required. He and his

colleagues have been arguing since 1982 that such events are possible.

And, he says, it might have happened right around the time the first

urban civilizations were crumbling.

Napier thinks a comet called Encke, discovered in 1786, is the

remnant of a larger comet that broke apart 5,000 years ago. Large

chunks and vast clouds of smaller debris were cast into space. Napier

said it's possible that Earth ran through that material during the

Early Bronze Age.

The night sky would have been lit up for years by a

fireworks-like display of comet fragments and dust vaporizing upon

impact with Earth's atmosphere. The Sun would have struggled to shine

through the debris. Napier has tied the possible event to a cooling of

the climate, measured in tree rings, that ran from 2354-2345 B.C.

Supporting evidence

Though no other craters have been found in the region and

precisely dated to this time, there is other evidence to suggest the

scenario is plausible. Two large impact craters in Argentina are

believed to have been created sometime in the past 5,000 years.

Benny Peiser, a social anthropologist at Liverpool John Moores

University in England, said roughly a dozen craters are known to have

been carved out during the past 10,000 years. Dating them precisely is

nearly impossible with current technology. And, Peiser said, whether

any of the impact craters thought to have been made in the past 10,000

years can be tied back to a single comet is still unknown.

But he did not discount Napier's scenario.

"There is no scientific reason to doubt that the break-up of a

giant comet might result in a shower of cosmic debris," Peiser said. He

also points out that because Earth is covered mostly by deep seas, each

visible crater represents more ominous statistical possibilities.

"For every crater discovered on land, we should expect two oceanic impacts with even worse consequences," he said.

Tsunamis generated in deep water can rise even taller when they reach a shore.

Reverberating today

Peiser studies known craters for clues to the past. But he also

examines religions and cults, old and new, for signs of what might have

happened way back then.

"I would not be surprised if the notorious rituals of human

sacrifice were a direct consequence of attempts to overcome this

trauma," he says of the South American impact craters. "Interestingly,

the same deadly cults were also established in the Near East during the

Bronze Age."

The impact of comets on myth and religion has reverberated through the ages, in Peiser's view.

"One has to take into consideration apocalyptic religions [of

today] to understand the far-reaching consequences of historical

impacts," he says. "After all, the apocalyptic fear of the end of the

world is still very prevalent today and can often lead to fanaticism

and extremism."

An obsession with the end of the world provides the legs on

which modern-day terrorism stands, Peiser argues. Leaders of

fundamentalist terror groups drum into the minds of their followers

looming cataclysms inspired by ancient writings. Phrases run along

these lines: a rolling up of the sun, darkening of the stars, movement

of the mountains, splitting of the sky.

No smoking gun yet

Despite the excitement of the newfound hole in the ground in

Iraq, it is still far from clear why so many civilizations collapsed in

such a relatively short historical time frame. Few scientists, even

those who find evidence to support the idea, are ready to categorically

blame a comet.

French soil scientist Marie-Agnes Courty, who in 1997 found

material that could only have come from a meteorite and dated it to the

Early Bronze Age, urged caution on drawing any conclusions until a

smoking gun has been positively identified.

"Certain scientists and the popular press do prefer the idea

of linking natural catastrophes and societal collapse," Courty said.

Multiple cosmic impacts are an attractive culprit though,

because of the many effects they can have, including some found in real

climate and geologic data. The initial impact, if it is on land,

vaporizes life for miles around. Earthquakes devastate an even wider

area. A cloud of debris can block out the Sun and alter the climate.

The extent and duration of the climate effects is not known for sure,

because scientists have never witnessed such an event.

It might not have taken much. Ancient civilizations, which depended on farming and reliable rainfall, were precarious.

Mike Baillie, a professor of palaeoecology at Queens University

in Belfast, figures it would have taken just a few bad years to destroy

such a society.

Even a single comet impact large enough to have created the

Iraqi crater, "would have caused a mini nuclear winter with failed

harvests and famine, bringing down any agriculture based populations

which can survive only as long as their stored food reserves," Baillie

said. "So any environmental downturn lasting longer than about three

years tends to bring down civilizations."

Other scientists doubt that a single impact would have altered the climate for so long.

Lessons for tomorrow

Either way, there is a giant scar on the planet, near the

cradle of civilization, that could soon begin to provide some solid

answers, assuming geologists can get permission to enter Iraq and

conduct a study.

"If the crater dated from the 3rd Millennium B.C., it would be

almost impossible not to connect it directly with the demise of the

Early Bronze Age civilizations in the Near East," said Peiser.

Perhaps before long all the cometary traditions, myths and

scientific fact will be seen to converge at the Iraqi hole in the

ground for good purpose. Understanding what happened, and how frequent

and deadly such impacts might be, is an important tool for researchers

like Peiser who aim to estimate future risk and help modern society avoid the fate of the ancients.

"Paradoxically, the Hebrew Bible and other Near Eastern documents have

kept alive the memory of ancient catastrophes whose scientific analysis

and understanding might now be vital for the protection of our own

civilizations from future impacts," Peiser said.

Charles Q. Choi

Space.com/Yahoo!News

Wed, 19 Dec 2007 07:39 UTC

The

infamous Tunguska explosion, which mysteriously leveled an area of

Siberian forest nearly the size of Tokyo a century ago, might have been

caused by an impacting asteroid far smaller than previously thought.

The fact that a relatively small asteroid could still cause such a massive explosion

suggests "we should be making more efforts at detecting the smaller

ones than we have till now," said researcher Mark Boslough, a physicist

at Sandia National Laboratory in Albuquerque, N.M.

The explosion near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River on June 30,

1908, flattened some 500,000 acres (2,000 square kilometers) of

Siberian forest. Scientists calculated the Tunguska explosion could

have been roughly as strong as 10 to 20 megatons of TNT - 1,000 times

more powerful than the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Wild theories have been bandied about for a century regarding what caused the Tunguska explosion,

including a UFO crash, antimatter, a black hole and famed inventor

Nikola Tesla's "death ray." In the last decade, researchers have

conjectured the event was triggered by an asteroid exploding in Earth's

atmosphere that was roughly 100 feet wide (30 meters) and 560,000

metric tons in mass - more than 10 times that of the Titanic.

The space rock is thought to have blown up above the surface, only fragments possibly striking the ground.

Now new supercomputer simulations suggest "the asteroid that caused the extensive damage

was much smaller than we had thought," Boslough said. Specifically, he

and his colleagues say it would have been a factor of three or four

smaller in mass and perhaps 65 feet (20 meters) in diameter.

The simulations run on Sandia's Red Storm supercomputer - the third fastest in the world - detail how an asteroid

that explodes as it runs into Earth's atmosphere will generate a

supersonic jet of expanding superheated gas. This fireball would have

caused blast waves that were stronger at the surface than previously

thought.

At the same time, previous estimates seem to have overstated

the devastation the event caused. The forest back then was not healthy,

according to foresters, "and it doesn't take as much energy to blow

down a diseased tree than a healthy tree," Boslough said. In addition,

the winds from the explosion

would naturally get amplified above ridgelines, making the explosion

seem more powerful than it actually was. What scientists had thought to

be an explosion between 10 and 20 megatons was more likely only three

to five megatons, he explained.

All in all, the researchers suggest that smaller asteroids may

pose a greater danger than previously believed. Moreover, "there are a

lot more objects that size," Boslough told SPACE.com.

NASA Ames Research Center planetary scientist and astrobiologist David Morrison, who did not participate in this study, said, "If

he's right, we can expect more Tunguska-sized explosions - perhaps

every couple of centuries instead of every millennia or two."

He added, "It raises the bar in the long term - ultimately, we'd like

to have a survey system that can detect things this small."

Boslough and his colleagues detailed their findings at the

American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco on Dec. 11. A paper

on the phenomenon has been accepted for publication in the International Journal of Impact Engineering.

Comment: Actually

it appears that small asteroids or comets hit the earth far more often

than thought or reported. Read the latest SOTT focus: New Light on the Black Death: The Cosmic Connection to get the idea...

A

pebble-sized meteorite crashed and burned into Earth, grazing

14-year-old Gerritt Blank while on his way to catch the school bus.

"At first, I only saw a big, white ball of light. Then, my hand hurt, and then it slammed into the street," he told daily Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung. "After I saw the white light, I felt something on my hand."

The result was a 10-centimetre burn on the back of his left hand, but Blank knew something special had happened to him.

"I thought the meteor struck me, but it could also be a result from the heat as it went by me," he said.

After the intial shock, Blank looked at the glowing rock that left a

sizable crater in Brakeler Wald Street. He then took the iced tea from

his school lunch and doused his glowing pebble and took it to school

with him.

"At school, I told the story. My classmates believed me," he

said. His parents didn't get to hear the story until the end of the

school day.

Once home, Blank, who plans to focus his studies in

science, tested the round, black object and already found some

confirmation the pebble is from outer space: like many meteorites, the

rock is magnetic.

Approximately 3,000 meteorites hit the Earth's surface daily.

Julian Ryall

National Geographic News

Thu, 11 Jun 2009 02:56 UTC

A

1,124-pound (510-kilogram) space probe will "collide" with our home

planet in June 2010 to simulate an approaching asteroid, Japanese

scientists have announced.

The Hayabusa spacecraft is currently on its way back to Earth

after a successful mission that landed on and hopefully collected

samples from the asteroid Itokawa.

Potential samples will be aboard a heat-resistant capsule that

will separate from Hayabusa shortly before re-entry into Earth's

atmosphere so they can be recovered. But experts say the main body of

the craft will most likely disintegrate during the trip through Earth's

atmosphere.

Although the plan was not part of Hayabusa's original

mission, scientists at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

recently decided to make the most of the doomed probe's return.

"Even though Hayabusa is not actually an asteroid, it will be

on a path that will cause it to collide with the Earth in the same way

as an asteroid," said JAXA spokesperson Akinori Hashimoto. "We will

monitor its movements, and the data will enable us to accurately

predict the future paths of asteroids that are on course to come close

to the Earth."

A Better Lookout

While other space agencies have programs for tracking asteroids

that might hit Earth, JAXA doesn't yet have the ability to monitor

these so-called near-Earth asteroids. So a team of researchers headed

by Makoto Yoshikawa has developed a prototype system to calculate the

trajectory, time, speed, and likelihood of an asteroid impact.

In October 2008, the team had a chance to test its system by

tracking asteroid 2008 TC3, an incoming space rock about 13 feet (4

meters) wide that astronomers at the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona had

spotted a few hours before it became a fireball in the skies over

Sudan.

Gerrit Blank survived a direct hit by a meteorite as it hurtled to Earth at more than 30,000 mph

A schoolboy has survived a direct hit by a meteorite after it fell to earth at 30,000mph.

Gerrit Blank, 14, was on his way to school when he saw "ball of light" heading straight towards him from the sky.

A red hot, pea-sized piece of rock then hit his hand before bouncing off and causing a foot wide crater in the ground.

The teenager survived the strike, the chances of which are just 1 in a

million - but with a nasty three-inch long scar on his hand.

He said: "At first I just saw a large ball of light, and then I suddenly felt a pain in my hand.

"Then a split second after that there was an enormous bang like a crash of thunder."

"The noise that came after the flash of light was so loud that my ears were ringing for hours afterwards.

"When it hit me it knocked me flying and then was still going fast enough to bury itself into the road," he explained.

Scientists are now studying the pea-sized meteorite which crashed to Earth in Essen, Germany.

"I am really keen on science and my teachers discovered that the fragment is really magnetic," said Gerrit.

Chemical tests on the rock have proved it had fallen from space.

Ansgar Kortem, director of Germany's Walter Hohmann Observatory, said:

"It's a real meteorite, therefore it is very valuable to collectors and

scientists.

"Most don't actually make it to ground level because they

evaporate in the atmosphere. Of those that do get through, about six

out of every seven of them land in water," he added.

The only other known example of a human being surviving a

meteor strike happened in Alabama, USA, in November 1954 when a

grapefruit-sized fragment crashed through the roof of a house, bounced

off furniture and landed on a sleeping woman.

Comment: Actually, these incidents are not as rare as we are made to believe. From our Comets and Catastrophe installment, read: Meteorites, Asteroids, and Comets: Damages, Disasters, Injuries, Deaths, and Very Close Calls

Press Association

Tue, 16 Jun 2009 12:37 UTC

Reports of strange lights in the English Channel overnight have been put down to a meteor shower, coastguards said.

Calls were made to stations from Hampshire down to Brixham in Devon and

across to Jersey and France at about 9.30pm on Monday, with people

saying they were seeing white and green flares in the sky.

A Solent Coastguard spokesman said: "There were reports of

flares all down the coast which went on for about half an hour but

there was a forecast for a meteor shower."

Meteor showers are caused by debris from a comet burning up in the Earth's atmosphere.

This can produce shooting stars across the night sky, particularly

visible on clear nights, which was the case over southern England on

Monday night.

Solent Coastguard said it could have been one of three showers forecast - the June Lyrids, the Ophruchids or the Zeta Pearseids.

John Hayes

UFOINFO

Mon, 15 Jun 2009 15:48 UTC

Posted: June 15, 2009

Date: May 23, 2009

Time: Approx: 6:00 a.m.

Number of witnesses: 2

Number of Objects: 1

Shape of Objects: Round

Full Description of Event/Sighting: Saw

what looked like a really large bright star in the sky. We were looking

in a easterly direction. My husband left and I continued to look up at

the bright light. It suddenly started to fade away like it was

something flying away.

We also saw a meteor or something enter the atmosphere around

the time of the Lyrid meteor shower. It has a fireball tail. We both

saw it. It was around 3:00am in the morning on I think the 22 April

2009. These are most probably both natural phenomenon?

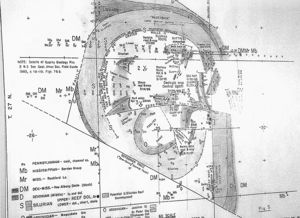

Geological map in the Benton County Stone office which shows the focal point of where a meteorite struck millions of years ago.

Several

years ago-well, about 65 to 97 million years ago-a gigantic meteorite

struck the earth just east of present-day Kentland in northwestern

Indiana's Benton County.

How big was the meteorite? The best guess is that it or

perhaps it was a comet ice mass left a circular crater dome measuring

about 4 ½ miles in diameter. The entire "disturbed area" is about eight miles in diameter.

The meteorite hit with such force and velocity that, as it plunged into

the earth, it lifted Shakopee dolomite (rock resembling limestone from

the Ordovician period) up to the planet's surface from some 2,000 feet

below. Much of this rock then stood vertically rather than

horizontally. Eventually, over the eons, glaciers and water eroded away

much of the crater, but still leaving numerous stone outcroppings.

It became what modern-day meteorologists and

geologists call the Kentland Crater, the fourth largest known impact

site in the United States. They've been studying the crater for the

past 70 years.

Here's the time to explain that, despite the evidence, some

believe what happened was not a meteorite strike but rather an

earthquake or explosion of gases erupting up through the earth's

surface.

Vertical structure in the Benton County Stone quarry is evident in this photo taken down in the quarry

In

more modern times, rock from the site was quarried, beginning around

1880. Mostly its major product was crushed stone for road building. It

still is a large working quarry today, operated by Rogers Group, Inc.,

as Newton County Stone.

Interest in the crater remains so strong that Susan Daniel,

community relations coordinator for the company, spends considerable

time conducting tours and answering questions about the crater.

While school children show up by the bus loads and geologists

and meteorologists still beat a path to the crater site, interestingly

enough many Hoosiers never have heard of it. As a matter of fact, I've

mentioned it to perhaps as many as 50 persons and only one had any idea

what I was talking about.

Nor is visiting the crater site the easiest thing to do.

If the area has had recent rain, passage down into the quarry

becomes difficult. My friend Howie Snider and I had to cancel three

proposed trips because of rain. Certainly you want to call Susan Daniel

to make arrangements for your visit.

Finally,

we had a good day. After showing us some rocks from the quarry and

explaining how the operation functions, Susan piled Howie and me into

her truck and away we went. First we traveled down in the quarry to the

raised platform where visitors usually are taken. It provides a

panoramic view.

I'm not sure I can describe the other twists and turns we took

as we explored other parts of the quarry. I was especially looking for

photo possibilities showing the vertical rock structure still visible

in a number of quarry walls.

Hard to believe but two hours had passed by the time when we returned to the quarry office.

Reports

of strange lights in the sky and distress flares being fired in the

English Channel actually turned out to be a meteor shower, coastguards

say.

Calls were made to coastguards across England's south coast,

including Cornwall, Devon and Hampshire, reporting white and green

flares.

Reports were also made to coastguards in Jersey and France for about 30 minutes from about 2130 BST on Monday.

Solent coastguards said three such showers had been forecast.

Meteor showers are caused by debris from a comet burning up in the Earth's atmosphere.

This can produce shooting stars across the night sky, particularly

visible on clear nights, which was the case over southern England on

Monday night.

Such showers can be forecast because the earth follows the same path around the Sun every year.

'Real treat'

This means it always crosses a comet trail at the same point in

its orbit and meteor showers can be seen at the same time every year.

A Solent Coastguard spokesman said: "There were reports of

flares all down the coast which went on for about half an hour but

there was a forecast for a meteor shower."

The spokesman said it could have been one of three showers forecast: the June Lyrids, the Ophruchids or the Zeta Perseids.

Round-the-world yachtswoman Dee Caffari and her all-women crew

were setting sail off the Isle of Wight at the time of the shower on an

attempt to break the round-Britain and Ireland record.

She said the display was "a real treat".

She said: "For a minute there last night I thought we had made such good progress that we were seeing the Northern Lights.

"We later learned that the pyrotechnic display was actually a meteor shower, which was an amazing sight."

Tudor Vieru

Softpedia

Tue, 16 Jun 2009 22:46 UTC

Captains have reported distress signals in the sky

A number of captains, sailing their ships in the crowded waters of the

English Channel on Monday night, signaled to the coastguard services in

France and the United Kingdom, saying that they noticed warning flares

in the night sky. The lights, they reported, were either white or

bright green, and they urged authorities to take steps to save the

ships in distress. The cause of the strange phenomenon, which began at

around 21:30 BST (2030 GMT), was quickly found to be an expected meteor

shower, of which the boat captains in the area had no idea.

Three successive meteor showers were visible yesterday, all coming from the same comet passing near our planet.

Astronomers had predicted the shower in advance, and this was made

possible by the fact that our planet takes roughly the same course

around the Sun every year. Comets and other celestial bodies slamming

into our planet's atmosphere are the things that produce what are known

as "shooting stars," swarms of meteorites that plummet to the ground at

large speeds, which causes them to burn up.

"There were reports of flares all down the coast which went on

for about half an hour, but there was a forecast for a meteor shower,"

a Solent Coastguard spokesman explained to the BBC News. Because most

meteor showers are regular occurrences in the evening skies, and are

particularly visible when there are no clouds, some of them have names.

The spokesman said that the one seen the night before might be either

June Lyrids, or the Ophruchids, or maybe the Zeta Perseids.

"For a minute there last night I thought we had made such good

progress that we were seeing the Northern Lights. We later learned that

the pyrotechnic display was actually a meteor shower, which was an

amazing sight," the British news agency quoted Dee Caffari, a

yachtswoman, as saying. She was sailing in the English Channel last

night as well, along with her all-women crew, in an attempt to break

the record at sailing around England and Ireland.

New York Times

Tue, 29 May 2001 16:03 UTC

In the early darkness of April 23, as Washington was beginning to relax

after the spy plane crisis in China, alarm bells began to go off on the

military system that monitors the globe for nuclear blasts.

Orbiting satellites that keep watch for nuclear attack had

detected a blinding flash of light over the Pacific several hundred

miles southwest of Los Angeles. On the ground, shock waves were strong

enough to register halfway around the world.

Tension reignited until the Pentagon could reassure official

Washington that the flash was not a nuclear blast. It was a speeding

meteoroid from outer space that had crashed into the earth's

atmosphere, where it exploded in an intense fireball.

"There was a big flurry of activity," recalled Dr. Douglas O.

ReVelle, a federal scientist who helps run the military detectors.

"Events like this don't happen all the time."

Preliminary estimates, Dr. ReVelle said, are that the cosmic

intruder was the third largest since the Pentagon began making global

satellite observations a quarter century ago. Its explosion in the

atmosphere had nearly the force of the atomic bomb dropped on

Hiroshima.

The episode shows how the system that warns of missile

attack and clandestine nuclear blasts is fast evolving to detect

bomb-size meteors as well. Now, it finds them about once a month, on

average. But Dr. ReVelle, a scientist at the Los Alamos National

Laboratory in New Mexico, said in an interview that the developing

system was likely to find many more of the natural blasts in the years

ahead.

"The real number is probably bigger," he said. "There's no doubt about that. But we don't know how much bigger."

Already, the system has shown that the planet is being

continually struck by large speeding rocks, and that the rate of

bombardment is higher than previously thought. The blasts light the sky

with brilliant fireballs but people seldom see the blasts because they

usually occur over the sea or uninhabited lands.

The rocky objects are anywhere from a few feet to about 80 feet wide.

They vanish in titanic explosions high in the atmosphere, their

enormous energy of motion converted almost instantly into vast amounts

of heat and light.

The Air Force did not publicly disclose its imaging of the

recent blast until late May, more than a month afterward. In a terse

release on May 25, its Technical Applications Center, at Patrick Air

Force Base in Florida, said the flash was "non- nuclear" and consistent

with past observed meteor explosions.

A Defense Department satellite, the Air Force said, detected bright flashes over a period of more than two seconds.

After that disclosure, Los Alamos got the military's permission to reveal its own detection of the April event. Its ground-based sensors are even more sensitive than orbiting satellites to the repercussions of meteor blasts.

The ground-based sensors work like sensitive ears to detect very

low-frequency sound waves, which radiate outward from an exploding rock

over hundreds and thousands of miles.

The sensors record sounds well below the range of human

hearing, including those from underground nuclear tests as well as

atmospheric blasts.

Dr. ReVelle said four arrays of the lab's sound sensors had

picked up the April blast. In addition, he said, sound detectors in Los

Angeles, Hawaii, Alaska, Canada and Germany had picked up its shock

waves. Two sensors in South America made tentative detections, he

added.

"It was a big event," he said. "There are people worrying

about impacts on the earth, and these things are giving us a better

understanding of the impact rate. That's the real byproduct

scientifically."

The speeding boulder was perhaps 12 feet wide, he added.

An even more sensitive global ear is emerging as the world's

nations try to monitor the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, a tentative

accord that seeks to end the exploding of nuclear arms and to police

compliance. When finished in the next year or so, the global acoustic

system is to consist of 60 arrays that give complete global coverage,

increasing the odds that even more large meteor impacts will be

detected.

The disclosure of such intruders is seen as bolstering the idea

that the earth is periodically subjected to strikes by even larger

objects, including doomsday rocks a few miles wide. Objects

this size are predicted to hit once every 10 million years or so,

causing mayhem and death on a planetary scale.

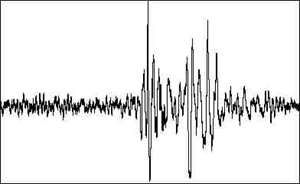

On April 23, 2001, scientists manning a network designed to detect

covert nuclear tests noticed something unusual - a very "loud" sound

coming from above the Pacific Ocean. This global network, consisting of

sensitive sound-recording instruments, had picked up on a large meteor

slamming into the atmosphere several hundred miles west of Baja

California, and exploding with a force comparable to that of the

nuclear bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

On Feb. 1, 2003, these same instruments heard something else -

the Space Shuttle Columbia reentering Earth's atmosphere on its tragic

final mission. NASA subsequently used those recordings to rule out

potential causes of the mission's demise, including a bolide or missile

impact.

The sensitive instruments that recorded the meteor's entrance

and the end of the Columbia record a range of low-frequency sound that

is inaudible to the human ear called infrasound. "It's sort of like

infrared light, which is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that

we can't see, in that it's the part of the sound spectrum that we can't

hear," says Michael Hedlin, a geophysicist and infrasound specialist at

the University of California, San Diego, and Scripps Institution of

Oceanography.

The instruments detect atmospheric noise, such as storms,

winds, volcanic eruptions, ocean waves and airplane traffic, and they

help scientists understand "just what's going on out there," Hedlin

says. "Right now, we're just listening to the world," he says, but

soon, the researchers will begin to more fully comprehend the

interactions between solid earth, the oceans and the atmosphere.

An explosive history

When the Krakatoa volcano erupted in Indonesia in 1883, the eruption

was so explosive that it sent low-frequency sound waves around the

world several times. Scientists noticed the sound waves through air

pressure changes measured by barometers. That was the first recorded

instance of infrasound.

Around the turn of the 20th century, scientists recorded a

giant meteor exploding above Russia. During World War II, the

instruments recorded aircraft movement and munitions explosions. During

the Cold War, scientists and the U.S. Department of Defense used the

instruments to monitor nuclear bomb tests in the atmosphere.

Then in the late 1960s, the application of infrasound for

monitoring nuclear tests around the world became limited by the

development of reliable satellite technology, which could see

atmospheric nuclear explosions and the subsequent onset of underground

testing, which was monitored by seismic data. "So the field sort of

went away for 30 years," says Milton Garces, a volcanologist,

oceanographer and infrasound specialist at the University of Hawaii.

"But luckily, there were a few individuals who kept the knowledge

alive," he says. And then, in 1996, the world adopted the Comprehensive

Test Ban Treaty, which brought about "a renaissance for infrasound,"

Garces says.

To enforce compliance with the treaty, the United Nations

created the International Monitoring System (IMS), a network of

geophysical sensor stations located around the world that monitor

seismic signals, atmospheric radioactive material releases,

hydroacoustic signals and infrasound, Hedlin says (Geotimes, October 2002). Luckily, he says, so far they haven't heard any nuclear tests - only a plethora of atmospheric sounds.

At work

Geophysicist

Michael Hedlin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography monitors an

international network of infrasound stations, like this one south of

Palm Springs, Calif. The sensitive instruments that measure

low-frequency sound waves resemble thermoses surrounded by wagon-wheel

spokes of PVC piping.

The IMS infrasound network will eventually contain about 60

stations somewhat evenly distributed around the world, but it is only

about one-third complete right now, Garces says. "We hope it'll be all

up and running in the next couple of years," he says, "but that might

be a little optimistic." Nevertheless, the scientists are already

recording more information than they can comprehend, he says.

The infrasound instruments (microbarometers) work similarly to

basic barometers that meteorologists use to detect weather patterns

through atmospheric pressures. Resembling large thermos bottles, the

microbarometers contain sensitive electronic instruments that convert

atmospheric pressure to an electric signal. The sensors are connected

to white wagon-wheel spokes of PVC piping that filter "unimportant

sounds from important sounds," Garces says, and keep animals and debris

away.

The instruments constantly measure ambient atmospheric sound

waves and transmit them to the International Data Center in Vienna,

Austria, which keeps all data related to the test ban treaty. The data

then go to a data center in McLean, Va., and also back to the lab that

operates the station, where the scientists do their own analysis

in-house, Garces says.

"Truthfully, most of the time we don't know what we're

listening to," says Henry Bass, a physicist and infrasound specialist

at the University of Mississippi. "We receive hundreds of thousands of

signals each year and we can only tell what a small fraction of them

are," he says. But the more the scientists listen, the better they get

at differentiating one sound from another and picking out the important

information from the clutter.

"Each station is kind of like your neighborhood," Garces says.

"You live there for a year and slowly begin to understand what's going

on, all of the idiosyncracies of your neighbors. You have that chatty

neighbor - you train yourself to cut out all the chatter and learn to

recognize what is important. That's what we do with each station."

After three years of continuous observation, the scientists

are now beginning to see patterns and differentiate the sounds

emanating from storm fronts, explosions, ocean waves, volcanoes and jet

airplanes. For example, Garces says, "the ocean is always singing in

this deep bass voice. Now we know what its tune is, so we can pick up

on swells and storms."

The researchers have also noticed strong seasonal patterns,

Hedlin says, which has been "really exciting." From the station nearest

San Diego, for example, the researchers hear a lot more signals from

the west in the winter and from the east in the summer, which is

related to seasonal wind patterns.

In general, stations will pick up atmospheric sounds from

hundreds to thousands of miles away, Hedlin says, but those data are

not well understood yet. The scientists monitoring the transmissions

can always tell the direction of the recording, but the distance is

harder to discern. Furthermore, depending on winds and the strength of

a signal, the stations can register waves from around the world.

Ash warnings

To

airplane pilots, ash escaping from erupting volcanoes, such as Mount

St. Helens (pictured here), can resemble normal clouds. Scientists can

use infrasound to divert planes around erupting volcanoes.

Hedlin, Garces and Bass work on a number of applications in

concert, although each has their own pet project. Hedlin pays close

attention to storms in the Pacific. Garces concentrates on infrasound

emitted from the constantly erupting Hawaiian volcanoes as well as

sounds of the ocean. Bass focuses on using infrasound to create a 3-D

image of the internal structures of the atmosphere (tomography).

Together, all three scientists are developing a project that uses

infrasound to create a volcanic ash warning system for airplanes.

When volcanoes erupt, they frequently lift large plumes of ash

and dust thousands of feet into the atmosphere. To a pilot, the ash and

dust can resemble regular clouds; however, if a plane flies into that

ash plume, the engines will fail. "Especially in volcanically active