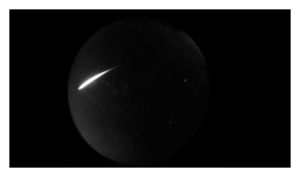

The first bright fireball of the New Year streaked over the southwestern USA on Jan. 1st at 03:15 UT. It was visible from Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico. "I was able to see it out my window," reports amateur astronomer Thomas Ashcraft from his rural observatory outside of Santa Fe. "It was brilliant turquoise blue." Ashcraft operates a combination all-sky camera/forward-scatter meteor radar system, which captured the fireball's flight. Click here to play the movie--and don't forget to turn up the volume to hear the ghostly radar echo:

Cameras belonging to NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network also recorded the fireball from multiple locations. An orbit calculated from those data show that the fireball was a random meteoriod hailing from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It hit Earth's atmosphere at 26 km/s (58,000 mph), which is relatively slow compared to other meteoroids, and disintegrated 82 km above Earth's surface.

"This was an auspicious start to 2012," says Ashcraft. "Clear skies and Happy New Year!"

Cameras belonging to NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network also recorded the fireball from multiple locations. An orbit calculated from those data show that the fireball was a random meteoriod hailing from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It hit Earth's atmosphere at 26 km/s (58,000 mph), which is relatively slow compared to other meteoroids, and disintegrated 82 km above Earth's surface.

"This was an auspicious start to 2012," says Ashcraft. "Clear skies and Happy New Year!"

Space mountain produces terrestrial meteorites

© NASA

A side view of Vesta's great south polar mountain.

When NASA's Dawn spacecraft entered orbit around giant asteroid Vesta in July, scientists fully expected the probe to reveal some surprising sights. But no one expected a 13-mile high mountain, two and a half times higher than Mount Everest, to be one of them.

A side view of Vesta's great south polar mountain.

When NASA's Dawn spacecraft entered orbit around giant asteroid Vesta in July, scientists fully expected the probe to reveal some surprising sights. But no one expected a 13-mile high mountain, two and a half times higher than Mount Everest, to be one of them.

For many years, researchers have been collecting Vesta meteorites from "fall sites" around the world. The rocks' chemical fingerprints leave little doubt that they came from the giant asteroid. Earth has been peppered by so many fragments of Vesta, that people have actually witnessed fireballs caused by the meteoroids tearing through our atmosphere. Recent examples include falls near the African village of Bilanga Yanga in October 1999 and outside Millbillillie, Australia, in October 1960.

"Those meteorites just might be pieces of the basin excavated when Vesta's giant mountain formed," says Dawn PI Chris Russell of UCLA.

Russell believes the mountain was created by a 'big bad impact' with a smaller body; material displaced in the smashup rebounded and expanded upward to form a towering peak. The same tremendous collision that created the mountain might have hurled splinters of Vesta toward Earth.

"Some of the meteorites in our museums and labs," he says, "could be fragments of Vesta formed in the impact -- pieces of the same stuff the mountain itself is made of."

To confirm the theory, Dawn's science team will try to prove that Vesta's meteorites came from the mountain's vicinity. It's a "match game" involving both age and chemistry.

© Russell/Earth and Planetary Sciences

Cross-section of the south polar mountain on Vesta with the cross sections of Olympus Mons on Mars, the largest mountain in the solar system, and the Big lsland of Hawaii as measured from the floor of the Pacific, the largest mountain on Earth. These latter two mountains are both shield volcanoes.

Cross-section of the south polar mountain on Vesta with the cross sections of Olympus Mons on Mars, the largest mountain in the solar system, and the Big lsland of Hawaii as measured from the floor of the Pacific, the largest mountain on Earth. These latter two mountains are both shield volcanoes.

The surface around the mountain, however, is tellingly smooth. Russell believes the impact wiped out the entire history of cratering in the vicinity. By counting craters that have accumulated since then, researchers can estimate the age of the landscape.

"In this way we can figure out the approximate age of the mountain's surface. Using radioactive dating, we can also tell when the meteorites were 'liberated' from Vesta. A match between those dates would be compelling evidence of a meteorite-mountain connection."

For more proof, the scientists will compare the meteorites' chemical makeup to that of the mountain area.

"Vesta is intrinsically but subtly colorful. Dawn's sensors can detect slight color variations in Vesta's minerals, so we can map regions of chemicals and minerals that have emerged on the surface. Then we'll compare these colors to those of the meteorites."

Could an impact on Vesta really fill so many museum display cases on Earth? Stay tuned for answers.

Brian Emfinger of Ozark, Arkansas, photographed this one on Jan. 2nd:

"Wow! What a really nice fireball," says Emfinger. "It emerged very very close to the Quadrantid radiant, but I'm not 100% sure it is indeed an early Quadrantid."

Even among professional researchers there is a lot of uncertainty about the Quadrantids. Because the shower occurs during the deep cold of northern winter, and because its peak is brief (often no longer than a couple of hours), this strong shower is seldom observed. Bill Cooke of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office hopes 2012 will be different. "We encourage sky watchers to be alert for Quadrantids and send their observations to NASA using the Meteor Counter app," he says. "With a little help, we just might learn something new about this intriguing shower."

© Paul Steinhardt, Princeton University

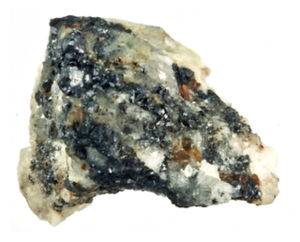

A rock sample containing quasicrystals unearthed in the Koryak Mountains in Russia.

A rock sample containing quasicrystals unearthed in the Koryak Mountains in Russia.

A rock fragment containing a previously unidentified natural quasicrystal may be the remnant of a meteorite that originated in the early solar system more than 4.5 billion years ago before Earth even existed.

Until now, researchers had assumed such quasicrystals, whose atoms are arranged in a quasi-regular pattern rather than the regular arrangement of atoms inside a crystal, were not feasible in nature. In fact, until now the only known quasicrystals were synthetic, formed in a laboratory under carefully controlled conditions. (This year's Nobel Prize in chemistry honored Dan Shechtman for his 1982 discovery of quasicrystals, which at the time were thought to break the laws of nature.)

"Many thought it had to be that way, because they thought quasicrystals are too delicate, too prone to crystallization, to form naturally," researcher Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University said. The new finding, described this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests "quasicrystals are much more common in the universe than we thought," Steinhardt added.

The rock was discovered in the Koryak Mountains of Russia. Various features of the quasicrystal suggest a meteorite origin, including the shapes of the grains and its chemical composition of metallic copper and aluminum that resemble those found in so-called carbonaceous chondrites; these are primitive meteorites that scientists think were remnants shed from the original building blocks of planets. Most meteorites found on Earth fit into this group.

Analysis of the quasicrystals revealed they were intermeshed with silicates and crystalline metals, with one quasicrystalline grain encased in a silica mineral called stishovite.

"Stishovite is silicon dioxide, the same chemical that makes quartz and sand, but here it forms a different structure that only occurs at high pressures achieved in meteorite collisions and impacts," wrote Steinhardt in an email to LiveScience.

The fact that the metallic aluminum was found in its unoxidized form was also surprising, since the metal has such a strong affinity for oxygen and couldn't have remained in that form here on Earth, Steinhardt said.

"So, we have learned that extraterrestrial conditions enable a phase of matter not likely possible on Earth. This raises the question: What other materials have been made in space that would not form naturally on Earth. In particular, are there other quasicrystals?" Steinhardt said.

This morning, Jan. 4th, Earth passed through a stream of debris from shattered comet 2003 EH1. The encounter produced a strong display of Quadrantid meteors over the Atlantic side of our planet, as many as 80 per hour according to the International Meteor Organization. Fredrik Broms caught this one streaking over his home in Kvaløya, Norway:

"The Quadrantids of 2012 were fantastic," says Broms. "The display was dominated by fairly bright and fast meteors."

NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network recorded 20 fireballs during the outburst. Data from multiple cameras allowed the orbits of the meteoroiuds to be calculated, and they are shown here in a diagram of the inner solar system:

More Images:

From Pete Lawrence of Selsey, West Sussex, UK; from Didier Schreiner of Wormhout, France; from Renata Arpasova of Avebury, Wiltshire, UK; from Glenn Wester of Smithtown, New York; from Yu Jun of Beijing, China; from Sylvain Weiller of Saint Rémy lès Chevreuse, France; from Fredrik Broms of Kvaløya, Norway; from Pete Glastonbury of Devizes, Wiltshire, UK; from Samuel Todd of Madison, Alabama; from Richard Hay of Green Cove Springs, Florida; from Amirreza Kamkar of Qayen, Iran

"The Quadrantids of 2012 were fantastic," says Broms. "The display was dominated by fairly bright and fast meteors."

NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network recorded 20 fireballs during the outburst. Data from multiple cameras allowed the orbits of the meteoroiuds to be calculated, and they are shown here in a diagram of the inner solar system:

More Images:

From Pete Lawrence of Selsey, West Sussex, UK; from Didier Schreiner of Wormhout, France; from Renata Arpasova of Avebury, Wiltshire, UK; from Glenn Wester of Smithtown, New York; from Yu Jun of Beijing, China; from Sylvain Weiller of Saint Rémy lès Chevreuse, France; from Fredrik Broms of Kvaløya, Norway; from Pete Glastonbury of Devizes, Wiltshire, UK; from Samuel Todd of Madison, Alabama; from Richard Hay of Green Cove Springs, Florida; from Amirreza Kamkar of Qayen, Iran

A large fireball was seen over southern Finland on Tuesday evening, reports a magazine published by the Ursa Astronomical Association. The ball, shining brighter than the moon, was visible for about ten seconds.

Ursa received numerous sightings of the fireball from various parts of southern and central Finland after 8:18pm on Tuesday.

The trajectory of the fireball is still being investigated. A mathematician of Ursa's fireball research group, Esko Lyytinen, gives a preliminary estimate that the phenomenon appeared over Narva in Estonia at the height of about 95km and vanished from sight around Heinola in southern Finland at the height of about 45-50km.

"We've had very good luck as the skies happened to clear at exactly the right moment and our automatic cameras recorded such a wonderful fireball. Otherwise, the whole night in Mikkeli was mostly cloudy," says Aki Taavitsainen, head of Ursa's Mikkeli office.

Ursa received numerous sightings of the fireball from various parts of southern and central Finland after 8:18pm on Tuesday.

The trajectory of the fireball is still being investigated. A mathematician of Ursa's fireball research group, Esko Lyytinen, gives a preliminary estimate that the phenomenon appeared over Narva in Estonia at the height of about 95km and vanished from sight around Heinola in southern Finland at the height of about 45-50km.

"We've had very good luck as the skies happened to clear at exactly the right moment and our automatic cameras recorded such a wonderful fireball. Otherwise, the whole night in Mikkeli was mostly cloudy," says Aki Taavitsainen, head of Ursa's Mikkeli office.

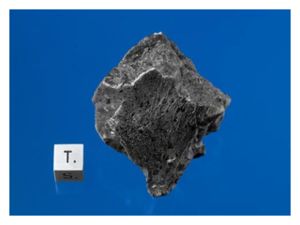

© Aki Taavitsainen ja Jani Lauanne, Mikkelin Ursa

A photo of the fireball snapped by Ursa's camera in Mikkeli.

US: Fireball Report Prompts Search of Island Marsh

Brunswick, Georgia. -- Authorities say they turned up nothing after Georgia State Patrol and U.S. Coast Guard crews searched a marsh off Jekyll Island for a possible plane crash.

The search began around 10 p.m. Wednesday, after someone reported seeing a fireball disappear in the marsh.

The Florida Times-Union reports the search was called off shortly after midnight early Thursday, and state patrol officials say it is believed the fireball might have been a meteor.

UK: Scientists Probe Mystery Boom and Earth Tremors in Northumberland and Scottish Borders

Experts are trying to determine what caused earth tremors and buildings to shake in Berwick and coastal areas of the Scottish Borders this afternoon.

Scientists can't say if it was an earthquake and the RAF said the RAF says none of their planes caused a sonic boom.

Seismologists are currently looking into the 3.15pm incident in Berwickshire and Northumberland.

A British Geological Survey spokeswoman said: "We know something happened as we've had lots of reports of the earth shaking and it registered on our equipment."

The data is being studied but the spokeswoman said they could not confirm if it was an earthquake or a sonic boom. But she said the data did not have the 'tell-tale' signs of an earthquake.

A Northumbria Police spokesman said that reports had come in from as far afield as south as Craster and that Lothian and Borders Police had received reports from Burnmouth.

He said that the RAF had reported that although planes were operating in the area it was not believed to be a sonic boom.

It has also been felt in Wooler and Belford as well as throughout Berwick.

Meteorites plummeting to earth? In Castro Valley?

It wasn't exactly pennies from heaven, but if the smoldering, dark-colored rock discovered on Mitch Medeiros' property did indeed fall from the sky, it may fetch the 55-year-old a fortune. If, that is, it's a verifiable meteorite.

Whatever it is has turned life upside down for the retired truck driver.

Medeiros said his phone has continued to ring since he told friends his dog -- an energetic 2-year-old black Labrador retriever named Bella -- led him Wednesday to a small dirt pile that was spewing steam in the backyard of his Castro Valley hills home.

"She was the one who found it. I never would have known," he said.

While Bella barked in excitement, Medeiros shoveled the rock out of a fresh, foot-deep hole. It was glowing "like a barbecue coal," he said.

He ran water to cool the jagged charcoal-colored rock, which is about 2 inches wide and 4 inches long.

He kept it in a cabinet for two days and didn't think much of it until he realized he could not answer a nagging question: Why would a normal rock glow?

"I've never seen one like that before," he said.

Medeiros, a married man with three children, telephoned Lawrence Livermore Laboratory for advice Friday morning.

"We get these kinds of calls maybe a couple of times a month and, more often than not, it turns out not to be a meteor," said Lynda Seaver, a lab spokeswoman.

Experts say that reports of meteorites are frequent, but like any valuable mineral, finding the real deal -- or any object plummeting from the sky -- is rare.

But it's possible, lab scientists told Medeiros. They advised him to chip off a piece of the rock and mail it to the University of New Mexico, where experts will use an electron microscope to determine the rock's properties, Medeiros said.

He since has stored the potentially valuable mineral in a bank safe-deposit box.

In the meantime, he has fielded a torrent of phone calls from aggressive members of a subculture he previously didn't know existed: meteorite collectors and dealers.

"I'm not even sure how they found out I had it," said Medeiros, who grew up in San Leandro.

Rare forms often end up in major museums and have sold for as much as $1,000 per gram -- well above the current price of gold, according to a meteorite-related website.

But he's not biting on any offers yet. It might be just another rock or a small piece of an old Russian spacecraft that has turned to junk in recent years.

On the advice of websites and Lawrence Lab scientists, Medeiros said he has put the rock through a number of tests.

A magnet, for example, did not stick to it and its excessive hardness broke off a hacksaw blade -- both good signs, experts told Medeiros.

"It's almost like cutting stainless steel, it just bounces off," he said.

The rock is so resistant it has made it difficult for him to break off a sample for official testing. But Medeiros is determined to find out and, he adds, he's growing more confident.

"It's passed at least three of the tests," he said. "It's a meteor."

Washington - Scientists are confirming a recent and rare invasion from Mars: meteorite chunks from the red planet that fell in Morocco last July.

This is only the fifth time scientists have chemically confirmed Martian meteorites that people witnessed falling. The small rock refugees were seen in a fireball in the sky six months ago, but they weren't discovered on the ground in North Africa until the end of December.

Scientists and collectors of meteorites are ecstatic and already the rocks are fetching big bucks because they are among the rarest things on Earth.

A special committee of meteorite experts, which includes some NASA scientists, confirmed the test results Tuesday. They certified that 15 pounds of meteorite recently collected came from Mars. The biggest rock weighs over 2 pounds.

Astronomers think millions of years ago something big smashed into Mars and sent rocks hurtling through the solar system. After a long journey through space, one of those rocks eventually landed here. It plunged into Earth's atmosphere, splitting into smaller pieces and one chunk shattered into shards when it hit the ground.

This is an important and unique hands-on look at Mars for scientists trying to learn about the planet's potential for life. So far, no NASA or Russian spacecraft have returned bits of Mars, so the only Martian samples scientists can examine are those that come here in a meteorite shower.

Most other samples had been on Earth for millions of years - or at the very least decades - which makes them tainted with Earth materials and life. These new rocks, while still likely contaminated because they have been on Earth for months, are still more pure and better to study.

The last time a Martian meteorite fell and was found fresh was in 1962. All the Martian rocks on Earth add up to less than 240 pounds.

The new samples were scooped up by dealers from those who found them. Even before the official certification, scientists at NASA, museums and universities scrambled to buy or trade these meteorites.

"It's a free sample from Mars, that's what these are, except you have to pay the dealers for it," said University of Alberta meteorite expert Chris Herd, who heads the committee that certified the discovery.

He's already bought a chunk of meteorite and said he was thrilled just to hold it, calling the rock "really spectacular."

One of the key decisions the scientists made Tuesday was to officially connect these rocks to the July fiery plunge witnessed by people and captured on video. The announcement and naming of these meteorites - called Tissint - came from the International Society for Meteoritics and Planetary Science, which is the official group of 950 scientists that confirms and names meteorites.

Meteorite dealer Darryl Pitt, who sold a chunk to Herd, said he charges from $11,000 to $22,500 an ounce and he's sold most of his already. At that price, the new Martian rock costs about 10 times more per ounce than gold.

In the past six months, it seems something has fallen from the sky every second minute. In September, the UARS satellite re-entered the Earth's atmosphere, causing a media frenzy. In October, the German satellite Rosat re-entered, with much less fanfare. Before Christmas, there were reports of space junk falling near Esperance in Western Australia.

And skywatchers were out in droves when the Quadrantid meteor shower put on its annual display earlier this month. Last weekend, the Russian Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, the country's 19th attempt to reach Mars, plunged back to Earth amid much speculation about the effects of its toxic fuel.

Near Earth Objects

We're getting used to the idea we're under continual bombardment from the heavens. But as well as objects from Earth orbit, there are some more sinister things to worry about: the nearly 8,000 identified Near Earth Objects (NEOs), asteroids, comets and meteoroids, whose orbits bring them close enough to Earth for collision to be a real risk. In November last year, the asteroid 2005 YU55 missed the Earth by a mere 300,000km.

So what are we doing about this? At a panel convened last week in Adelaide by the International Space University's Southern Hemisphere Summer Space Program, experts noted that our knowledge about what's "out there" has increased exponentially in recent decades. We've got a pretty good idea of what is roaming around in the Near Earth environment.

But as they also pointed out, very little is actively being done in the Southern Hemisphere to track and prepare for events such as re-entries.

It wasn't always this way: until 1996, the Australian government funded a Spaceguard program, which was responsible for identifying one-third of all catalogued NEOs - a very impressive track record. There are currently calls to revive Spaceguard activities, bringing Australia more into line with international efforts. (And in the meantime, it looks as if Australia will participate in talks with the US and Europe to help address the space junk issue.)

Australia is indeed very well placed, in terms of its location, size, expertise and availability of radio-quiet areas, to play an important role in observing and tracking both natural and human-manufactured objects in space. It's also one of the few countries that has direct experience in what happens when a spacecraft makes an uncontrolled re-entry over land.

In 1979, Skylab, one of the largest spacecraft ever launched at that time, fell out of the sky in flaming fragments over Western Australia. No-one was hurt and there was no property damage, although the Shire of Esperance famously fined the US State Department $400 for littering. (The fine was finally paid in 2009 by public donations).

Hit and miss

The first thing to note is that you would have to be very unlucky indeed to have a piece of space junk fall on you. It's only happened once that we know of. According to the Centre for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies (CORDS), Lottie Williams of Oklahoma was hit by a small piece of a Delta II rocket as she was taking a walk one day in 1996. She was unharmed. Similarly, there are no accounts of people being injured by meteorites. There's just so much ocean, desert and ice - and this is usually where the stuff lands.

Accounts of Skylab's re-entry, however, can be used to derive some indications about what to expect. Sonic booms typically accompany objects falling at high speed through the upper atmosphere. As with fireworks, these loud noises can upset domestic pets and livestock. Take the same precautions as you would for your pets on New Year's Eve; there is plenty of information about this online.

Falling meteorites have frequently been blamed for causing fires, and this was also a concern for people in the debris footprint of Skylab. Having an up-to-date fire plan and managing the local risk around your house in terms of available fuel are the best way to prepare for this.

If spacecraft fragments fall near you, don't rush to collect them. For a start, there may be toxic fuel residues or metals such as beryllium, or radioactive material from power sources and onboard experiments. The most common spacecraft components to survive re-entry are spherical titanium pressure vessels.

Usually regarded as an inert metal, titanium is now thought to have dangerous corrosion products. There are no recorded instances of people falling ill from contact with space junk, but there's no point taking the risk.

As appealing as the idea of having a personal souvenir of space is, this is not technically junk. Under the terms of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the fragments belong to the country which launched the spacecraft. So don't collect fragments and sell them on eBay - as people may well have done if the internet existed in 1979. (But, if you are really keen, you can still buy tiny pieces of Skylab encased in resin with an authentification certificate today). The pieces can be used to analyse the re-entry event, and perhaps what went wrong with the spacecraft.

If you or your property have been damaged by the spacecraft, you may be entitled to compensation. It will be the responsibility of the appropriate government agency to negotiate what happens next. For most countries, this will be the national space agency. The closest Australia has at the moment is the Space Policy Unit based in Canberra.

Next time you hear that a spacecraft might fall on Australia, don't be too alarmed. Keep an eye on the predictions, bring your kittens inside, and rejoice in the fact that there is one less object clogging up Earth's orbit. If you are concerned about NEOs, join those lobbying for the reinstatement of Spaceguard.

It's not all doom and gloom. The stuff that falls from space reminds us we are part of the cosmos too.

Alice Gorman is a faculty member of the International Space University Southern Hemisphere Summer Space Program.

North Carolina, US: Mystery "Boom" Reported in Lenoir County

Kinston - We've received calls and Facebook messages about a loud "boom" heard shortly before noon in parts of Lenoir county, but so far officials say they aren't sure what caused the loud noise.

Some are speculating it was a sonic boom caused by a plane.

Several callers say it was so intense it shook the walls of local businesses.

According to reports, the loud noise was heard in various parts of Lenoir County including LaGrange and various parts of Kinston near Lenior Community College.

Local officials told "Nine on Your Side" they are unsure what caused the noise.

A small asteroid will pass extremely close to Earth tomorrow (January 27, 2012). Named 2012 BX34, this 8 meter- (26-foot-) wide space rock will skim Earth less than 60,000 km (37,000 miles, .0004 AU), at around 16:00 UTC, according to the Minor Planet Center. The latest estimates have it traveling at about about 500 meters/minute (1,643.17 ft/minute). 2012 BX34 has been observed by the Catalina Sky Survey and the Mt. Lemmon Survey in Arizona, and the Magdalena Ridge Observatory in New Mexico, so its orbit is well defined and there is no risk of impact to Earth.

Amateur astronomers in the right place and time could view this object, as it should be about magnitude 14 at the time of closest approach. Nick Howes, with the Faulkes Telescope Project said his team is hoping to observe and image the asteroid, and we hope to share their images later.

An asteroid about the size of a bus shaved by Earth on Friday in what space watchers described as a "near-miss," though experts were not concerned about the possibility of an impact.

An asteroid about the size of a bus shaved by Earth on Friday in what space watchers described as a "near-miss," though experts were not concerned about the possibility of an impact.

The asteroid, named 2012 BX34, measured between six and 19 meters in diameter (20 to 62 feet), said Gareth Williams, associate director of the U.S.-based Minor Planet Center which tracks space objects.

The asteroid, which had been unknown before it popped into view from a telescope in Arizona on Wednesday, came within about 60,000 kilometers (37,000 miles) of Earth on Friday at about 1500 GMT, he said.

"It's a near miss. It makes the top 20 list of closest approaches ever observed," Williams told AFP.

NASA had announced on Twitter on Thursday that the asteroid would "safely pass Earth on January 27."

Williams explained that since the asteroid was so small, it could only be detected when it was close to the Earth, but that the fly-by, while a surprise, was not terribly uncommon.

"This came about a sixth of the distance from the Moon," he said. "In the past year we have had some 30 objects that were observed to come within the orbit of the Moon."

Williams said his pager went off in the middle of the night Wednesday after the asteroid was first sighted, but once he checked he went right back to sleep because he knew it would not hit Earth from its projected distance.

Comment: Oh well that's alright then! Go back to sleep folks, nothing to see here! Just ANOTHER asteroid from deep space whizzing past us!

But where it goes next is less certain.

"If we have radar on it from last night then we can probably predict it decades into the future," he said.

"If we don't have radar, then we only have a two- to three-day arc of observations and extrapolating that into the future will be very uncertain."

However, since the asteroid is so diminutive, it poses little threat to the vast Earth, he added.

"This object is so small that even if it hits us the next time around it won't survive passage through the atmosphere in one piece," Williams said.

"Objects in that size range -- six to 19 meters -- will typically break up due to the force of entering the atmosphere. All that may remain are a few fist- or football-sized rocks that make it to the ground as meteorites."

In November last year, a much a larger asteroid called 2005 YU55 made its closest fly-by of Earth in 200 years.

The near-spherical asteroid, 1,300 feet (400 meters) in diameter, passed by at a distance of 201,700 miles (324,600 kilometers), as measured from the center of Earth, NASA said.

In 2008, a small asteroid estimated to be a few meters (yards) wide sparked a fireball in the night sky plunged down over Sudan, scattering fragments over the Nubian desert, NASA said.

These Pesky Cometary...err...Satellite Fragments: Space Station's Orbit Raised to Avoid Collision with Space Junk

Comment: A rare event? Somebody hasn't been keeping up with SOTT.net!

Video: What was that thing?! Enormous fireball entering atmosphere over Northern Europe on Christmas Eve 2011

A photo of the fireball snapped by Ursa's camera in Mikkeli.

This morning, Jan. 4th, Earth passed through a stream of debris from shattered comet 2003 EH1. The encounter produced a strong display of Quadrantid meteors over the Atlantic side of our planet, as many as 80 per hour according to the International Meteor Organization. Fredrik Broms caught this one streaking over his home in Kvaløya, Norway:

"The Quadrantids of 2012 were fantastic," says Broms. "The display was dominated by fairly bright and fast meteors."

NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network recorded 20 fireballs during the outburst. Data from multiple cameras allowed the orbits of the meteoroiuds to be calculated, and they are shown here in a diagram of the inner solar system:

More Images:

From Pete Lawrence of Selsey, West Sussex, UK; from Didier Schreiner of Wormhout, France; from Renata Arpasova of Avebury, Wiltshire, UK; from Glenn Wester of Smithtown, New York; from Yu Jun of Beijing, China; from Sylvain Weiller of Saint Rémy lès Chevreuse, France; from Fredrik Broms of Kvaløya, Norway; from Pete Glastonbury of Devizes, Wiltshire, UK; from Samuel Todd of Madison, Alabama; from Richard Hay of Green Cove Springs, Florida; from Amirreza Kamkar of Qayen, Iran

Parts of a fireball seen in Finnish skies on Tuesday evening have fallen in central Finland. According to the Finnish astronomy magazine Tähdet ja Avaruus (Stars and Space), the fireball fragmented, with the majority of pieces falling near the centre of Jämsä town.

The largest pieces to land on earth weighed about one kilogram, according to calculations made by the meteorite section of Ursa Astronomical Association. Snow may have covered signs of the landings. However, meteorite fragments could still be found.

According to Stars and Space magazine, it is rare to have meteorite impact close to large populated areas in Finland. A similar event last took place over a hundred years ago, when meteorites fell near the town of Mikkeli.

The meteorites in the vicinity of Jämsä originate in a larger body that entered the earth's atmosphere around Narva in Estonia. The velocity of the object was about 19 kilometres per second, which is relatively low.

The daily paper Iltalehti first reported on the meteorite in Finland.

Mexico: Authorities Search for Meteorite that Fell on Northwest Mexico

Culiacan - Mexican authorities are searching for a meteorite that fell to earth in a rural area in the northwestern part of the country, which was sighted in the region but about which there are as yet few details, officials said Friday.

The alarm sounded when inhabitants of a mountainous region of Sinaloa state near the border with Chihuahua were startled by the approach of a luminous object in the night sky.

NASA and Mexican emergency services agencies confirmed that the object was a meteorite, whose dimensions and exact place of impact are unknown.

Some witnesses believed it could have crashed to earth between the Gustavo Diaz Ordaz Dam and the town of San Jose de Gracia.

After hours of searching by air and land, an official of the Sinaloa municipality of Sinaloa, Marcial Alvarez, told Efe that the meteorite is believed to have impacted next door in Chihuahua state.

This Saturday observers will fly over the area in search of the meteorite.

It would not be the first time Sinaloa has seen a phenomenon like this. In 1871 a meteorite fell on the settlement of Bacubirito, which with a weight of 22 tons is considered one of the biggest in the world.

"The Quadrantids of 2012 were fantastic," says Broms. "The display was dominated by fairly bright and fast meteors."

NASA's All-Sky Fireball Network recorded 20 fireballs during the outburst. Data from multiple cameras allowed the orbits of the meteoroiuds to be calculated, and they are shown here in a diagram of the inner solar system:

More Images:

From Pete Lawrence of Selsey, West Sussex, UK; from Didier Schreiner of Wormhout, France; from Renata Arpasova of Avebury, Wiltshire, UK; from Glenn Wester of Smithtown, New York; from Yu Jun of Beijing, China; from Sylvain Weiller of Saint Rémy lès Chevreuse, France; from Fredrik Broms of Kvaløya, Norway; from Pete Glastonbury of Devizes, Wiltshire, UK; from Samuel Todd of Madison, Alabama; from Richard Hay of Green Cove Springs, Florida; from Amirreza Kamkar of Qayen, Iran

The largest pieces to land on earth weighed about one kilogram, according to calculations made by the meteorite section of Ursa Astronomical Association. Snow may have covered signs of the landings. However, meteorite fragments could still be found.

According to Stars and Space magazine, it is rare to have meteorite impact close to large populated areas in Finland. A similar event last took place over a hundred years ago, when meteorites fell near the town of Mikkeli.

The meteorites in the vicinity of Jämsä originate in a larger body that entered the earth's atmosphere around Narva in Estonia. The velocity of the object was about 19 kilometres per second, which is relatively low.

The daily paper Iltalehti first reported on the meteorite in Finland.

Mexico: Authorities Search for Meteorite that Fell on Northwest Mexico

The alarm sounded when inhabitants of a mountainous region of Sinaloa state near the border with Chihuahua were startled by the approach of a luminous object in the night sky.

NASA and Mexican emergency services agencies confirmed that the object was a meteorite, whose dimensions and exact place of impact are unknown.

Some witnesses believed it could have crashed to earth between the Gustavo Diaz Ordaz Dam and the town of San Jose de Gracia.

After hours of searching by air and land, an official of the Sinaloa municipality of Sinaloa, Marcial Alvarez, told Efe that the meteorite is believed to have impacted next door in Chihuahua state.

This Saturday observers will fly over the area in search of the meteorite.

It would not be the first time Sinaloa has seen a phenomenon like this. In 1871 a meteorite fell on the settlement of Bacubirito, which with a weight of 22 tons is considered one of the biggest in the world.

US: Fireball Report Prompts Search of Island Marsh

The search began around 10 p.m. Wednesday, after someone reported seeing a fireball disappear in the marsh.

The Florida Times-Union reports the search was called off shortly after midnight early Thursday, and state patrol officials say it is believed the fireball might have been a meteor.

UK: Scientists Probe Mystery Boom and Earth Tremors in Northumberland and Scottish Borders

Scientists can't say if it was an earthquake and the RAF said the RAF says none of their planes caused a sonic boom.

Seismologists are currently looking into the 3.15pm incident in Berwickshire and Northumberland.

A British Geological Survey spokeswoman said: "We know something happened as we've had lots of reports of the earth shaking and it registered on our equipment."

The data is being studied but the spokeswoman said they could not confirm if it was an earthquake or a sonic boom. But she said the data did not have the 'tell-tale' signs of an earthquake.

A Northumbria Police spokesman said that reports had come in from as far afield as south as Craster and that Lothian and Borders Police had received reports from Burnmouth.

He said that the RAF had reported that although planes were operating in the area it was not believed to be a sonic boom.

It has also been felt in Wooler and Belford as well as throughout Berwick.

Comet Lovejoy - Some Comets like it Hot

Comets are icy and fragile. They spend most of their time orbiting through the dark outskirts of the solar system safe from destructive rays of intense sunlight. The deepest cold is their natural habitat.

Last November amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy discovered a different kind of comet. The icy fuzzball he spotted in the sky over his backyard observatory in Australia was heading almost directly for the sun. On Dec. 16th, less than three weeks after he found it, Comet Lovejoy would swoop through the sun's atmosphere only 120,000 km above the stellar surface.

Astronomers soon realized a startling fact: Comet Lovejoy likes it hot.

"Terry found a sungrazer," says Karl Battams of the Naval Research Lab in Washington DC. "We figured its nucleus was about as wide as two football fields - the biggest such comet in nearly 40 years."

Sungrazing comets aren't a new thing. In fact, the orbiting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) watches one fall toward the sun and evaporate every few days. These frequent kamikaze comets, known as "Kreutz sungrazers," are thought to be splinters of a giant comet that broke apart hundreds of years ago. Typically they measure about 10 meters across, small, fragile, and easily vaporized by solar heat.

Sungrazing comets aren't a new thing. In fact, the orbiting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) watches one fall toward the sun and evaporate every few days. These frequent kamikaze comets, known as "Kreutz sungrazers," are thought to be splinters of a giant comet that broke apart hundreds of years ago. Typically they measure about 10 meters across, small, fragile, and easily vaporized by solar heat.

Based on its orbit, Comet Lovejoy was surely a member of the same family - except it was 200 meters wide instead of the usual 10. Astronomers were eager to see such a whopper disintegrate. Even with its extra girth, there was little doubt that it would be destroyed.

When Dec. 16th came, however, "Comet Lovejoy shocked us all," says Battams. "It survived, and even flourished."

Images from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory showed the comet vaporizing furiously as it entered the sun's atmosphere--apparently on the verge of obliteration - yet Comet Lovejoy was still intact when it emerged on the other side. The comet had lost its tail during the fiery transit--a temporary setback. Within hours, the tail grew back, bigger and brighter than before.

"It's fair to say we were dumbfounded," says Matthew Knight of the Lowell Observatory and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. "Comet Lovejoy must have been bigger than we thought, perhaps as much as 500 meters wide."

That would make it the biggest sungrazer since Comet Ikeya-Seka almost 40 years ago. With a tail that stretched halfway across the sky, Ikeya-Seki was actually visible in broad daylight after it passed through the sun's atmosphere in October 1965. In Japan, where observers spotted the over-heated comet only 1/2 degree from the sun, it was described as 10 times brighter than the Full Moon.

Comet Lovejoy wasn't that bright, but it was still amazing. Only a few days after it left the sun, the comet showed up in the morning skies of the southern hemisphere. Observers in Australia, South America, South Africa, and New Zealand likened it to a search light beaming up from the east before dawn. The tail lined up parallel to the Milky Way and, for a few days, made it seem that we lived in a double-decker galaxy.

Astronauts on the International Space Station also witnessed the comet. ISS Commander Dan Burbank, who has seen his share of wonders, even once flying directly through the Northern Lights onboard the space shuttle, declared Comet Lovejoy "the most amazing thing I have ever seen in space."

Astronauts on the International Space Station also witnessed the comet. ISS Commander Dan Burbank, who has seen his share of wonders, even once flying directly through the Northern Lights onboard the space shuttle, declared Comet Lovejoy "the most amazing thing I have ever seen in space."

An armada of spacecraft including SOHO, the Solar Dynamics Observatory, NASA's twin STEREO probes, Japan's Hinode spacecraft, and Europe's Proba2 microsatellite recorded the historic event.

"We've collected a mountain of data," says Knight. "But there are some things we're still having trouble explaining."

For instance, what made Lovejoy's tail wiggle so wildly when it entered the solar corona? Perhaps it was in the grip of the sun's powerful magnetic field.

What caused Lovejoy to lose its tail inside the sun's atmosphere - and then regain it later? "This is one of the biggest mysteries to me," says Battams.

And then there is the ultimate existential puzzle: How did Comet Lovejoy survive at all?

As January unfolds, the "Comet that liked it Hot" is returning to the outer solar system, still intact, leaving many mysteries behind. "It'll be back in about 600 years," says Knight. "Maybe we will have figured them out by then."

Last November amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy discovered a different kind of comet. The icy fuzzball he spotted in the sky over his backyard observatory in Australia was heading almost directly for the sun. On Dec. 16th, less than three weeks after he found it, Comet Lovejoy would swoop through the sun's atmosphere only 120,000 km above the stellar surface.

Astronomers soon realized a startling fact: Comet Lovejoy likes it hot.

"Terry found a sungrazer," says Karl Battams of the Naval Research Lab in Washington DC. "We figured its nucleus was about as wide as two football fields - the biggest such comet in nearly 40 years."

© Wayne-England

Comet Lovejoy at sunrise on Dec. 25, 2011. Wayne England took the picture from Poocher Swamp, west of Bordertown, South Australia.

Comet Lovejoy at sunrise on Dec. 25, 2011. Wayne England took the picture from Poocher Swamp, west of Bordertown, South Australia.

Based on its orbit, Comet Lovejoy was surely a member of the same family - except it was 200 meters wide instead of the usual 10. Astronomers were eager to see such a whopper disintegrate. Even with its extra girth, there was little doubt that it would be destroyed.

When Dec. 16th came, however, "Comet Lovejoy shocked us all," says Battams. "It survived, and even flourished."

Images from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory showed the comet vaporizing furiously as it entered the sun's atmosphere--apparently on the verge of obliteration - yet Comet Lovejoy was still intact when it emerged on the other side. The comet had lost its tail during the fiery transit--a temporary setback. Within hours, the tail grew back, bigger and brighter than before.

"It's fair to say we were dumbfounded," says Matthew Knight of the Lowell Observatory and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab. "Comet Lovejoy must have been bigger than we thought, perhaps as much as 500 meters wide."

That would make it the biggest sungrazer since Comet Ikeya-Seka almost 40 years ago. With a tail that stretched halfway across the sky, Ikeya-Seki was actually visible in broad daylight after it passed through the sun's atmosphere in October 1965. In Japan, where observers spotted the over-heated comet only 1/2 degree from the sun, it was described as 10 times brighter than the Full Moon.

Comet Lovejoy wasn't that bright, but it was still amazing. Only a few days after it left the sun, the comet showed up in the morning skies of the southern hemisphere. Observers in Australia, South America, South Africa, and New Zealand likened it to a search light beaming up from the east before dawn. The tail lined up parallel to the Milky Way and, for a few days, made it seem that we lived in a double-decker galaxy.

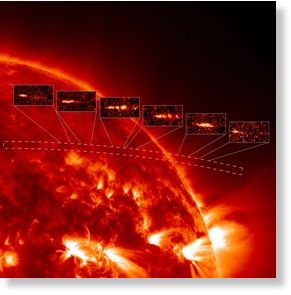

© NASA

This sequence of images, gathered by an extreme UV telescope onboard NASA's STEREO-B spacecraft, shows Comet Lovejoy's tail wiggling wildly in transit through the solar corona.

Animated Version

This sequence of images, gathered by an extreme UV telescope onboard NASA's STEREO-B spacecraft, shows Comet Lovejoy's tail wiggling wildly in transit through the solar corona.

Animated Version

An armada of spacecraft including SOHO, the Solar Dynamics Observatory, NASA's twin STEREO probes, Japan's Hinode spacecraft, and Europe's Proba2 microsatellite recorded the historic event.

"We've collected a mountain of data," says Knight. "But there are some things we're still having trouble explaining."

For instance, what made Lovejoy's tail wiggle so wildly when it entered the solar corona? Perhaps it was in the grip of the sun's powerful magnetic field.

What caused Lovejoy to lose its tail inside the sun's atmosphere - and then regain it later? "This is one of the biggest mysteries to me," says Battams.

And then there is the ultimate existential puzzle: How did Comet Lovejoy survive at all?

As January unfolds, the "Comet that liked it Hot" is returning to the outer solar system, still intact, leaving many mysteries behind. "It'll be back in about 600 years," says Knight. "Maybe we will have figured them out by then."

Did you see that ball of white that flew through the sky Friday morning?

Our newsroom was getting calls, emails, and tweets from listeners, and some are convinced they saw a meteor at around 7:30am.

"I saw this huge flash come right across the sky going west to east," says James, who was driving near Thorsby at the time. "Just by chance I caught the whole thing. It was very, very bright and very low to the ground."

Most callers agree that the light disappeared as quickly as it came.

"This was quite bright -- a big chunk of white," says Pat, who was driving on 153 Avenue near Castledowns Road. "(It only lasted) about two or three seconds. They go fast. You notice them, and then before it hit the ground or before it disappeared near the horizon, it was out."

Frank Florian from the Telus World of Science didn't see it, but by the description he's fairly confident that this was a meteor.

"They're usually short-lived, traveling very swiftly, usually taking anywhere from two to five seconds to go across the sky, very similar in nature to the 2008 fireball that was seen over much of Alberta and some of the northern states," says Florian.

There have been reported sightings from Thorsby to Gibbons to Mundare to Lac la Biche. And when you can see it across such a broad area, Florian says that means it was likely still hundreds, even thousands, of kilometres away.

"In terms of actually seeing it yourself, I'd say it's a little bit more on the rare side," says Florian, who wants to hear from anyone who caught a glimpse of the meteor. "In terms of how common things like this are passing through the earth's atmosphere, it happens every night. Every single day around the world, things are always hitting the earth, it's just a matter of you being outside at the right time."

Our newsroom was getting calls, emails, and tweets from listeners, and some are convinced they saw a meteor at around 7:30am.

"I saw this huge flash come right across the sky going west to east," says James, who was driving near Thorsby at the time. "Just by chance I caught the whole thing. It was very, very bright and very low to the ground."

Most callers agree that the light disappeared as quickly as it came.

"This was quite bright -- a big chunk of white," says Pat, who was driving on 153 Avenue near Castledowns Road. "(It only lasted) about two or three seconds. They go fast. You notice them, and then before it hit the ground or before it disappeared near the horizon, it was out."

Frank Florian from the Telus World of Science didn't see it, but by the description he's fairly confident that this was a meteor.

"They're usually short-lived, traveling very swiftly, usually taking anywhere from two to five seconds to go across the sky, very similar in nature to the 2008 fireball that was seen over much of Alberta and some of the northern states," says Florian.

There have been reported sightings from Thorsby to Gibbons to Mundare to Lac la Biche. And when you can see it across such a broad area, Florian says that means it was likely still hundreds, even thousands, of kilometres away.

"In terms of actually seeing it yourself, I'd say it's a little bit more on the rare side," says Florian, who wants to hear from anyone who caught a glimpse of the meteor. "In terms of how common things like this are passing through the earth's atmosphere, it happens every night. Every single day around the world, things are always hitting the earth, it's just a matter of you being outside at the right time."

© Anda Chu

Mitch Medeiros, of Castro Valley, holds a two-pound rock that may be a meteorite in Castro Valley, Calif. Friday Jan. 13, 2012. Medeiros found the rock in his backyard Wednesday and phoned Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Friday morning. The lab is working with Medeiros to help him identify the rock.

Mitch Medeiros, of Castro Valley, holds a two-pound rock that may be a meteorite in Castro Valley, Calif. Friday Jan. 13, 2012. Medeiros found the rock in his backyard Wednesday and phoned Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Friday morning. The lab is working with Medeiros to help him identify the rock.

Meteorites plummeting to earth? In Castro Valley?

It wasn't exactly pennies from heaven, but if the smoldering, dark-colored rock discovered on Mitch Medeiros' property did indeed fall from the sky, it may fetch the 55-year-old a fortune. If, that is, it's a verifiable meteorite.

Whatever it is has turned life upside down for the retired truck driver.

Medeiros said his phone has continued to ring since he told friends his dog -- an energetic 2-year-old black Labrador retriever named Bella -- led him Wednesday to a small dirt pile that was spewing steam in the backyard of his Castro Valley hills home.

"She was the one who found it. I never would have known," he said.

While Bella barked in excitement, Medeiros shoveled the rock out of a fresh, foot-deep hole. It was glowing "like a barbecue coal," he said.

He ran water to cool the jagged charcoal-colored rock, which is about 2 inches wide and 4 inches long.

He kept it in a cabinet for two days and didn't think much of it until he realized he could not answer a nagging question: Why would a normal rock glow?

"I've never seen one like that before," he said.

Medeiros, a married man with three children, telephoned Lawrence Livermore Laboratory for advice Friday morning.

"We get these kinds of calls maybe a couple of times a month and, more often than not, it turns out not to be a meteor," said Lynda Seaver, a lab spokeswoman.

Experts say that reports of meteorites are frequent, but like any valuable mineral, finding the real deal -- or any object plummeting from the sky -- is rare.

But it's possible, lab scientists told Medeiros. They advised him to chip off a piece of the rock and mail it to the University of New Mexico, where experts will use an electron microscope to determine the rock's properties, Medeiros said.

He since has stored the potentially valuable mineral in a bank safe-deposit box.

In the meantime, he has fielded a torrent of phone calls from aggressive members of a subculture he previously didn't know existed: meteorite collectors and dealers.

"I'm not even sure how they found out I had it," said Medeiros, who grew up in San Leandro.

Rare forms often end up in major museums and have sold for as much as $1,000 per gram -- well above the current price of gold, according to a meteorite-related website.

But he's not biting on any offers yet. It might be just another rock or a small piece of an old Russian spacecraft that has turned to junk in recent years.

On the advice of websites and Lawrence Lab scientists, Medeiros said he has put the rock through a number of tests.

A magnet, for example, did not stick to it and its excessive hardness broke off a hacksaw blade -- both good signs, experts told Medeiros.

"It's almost like cutting stainless steel, it just bounces off," he said.

The rock is so resistant it has made it difficult for him to break off a sample for official testing. But Medeiros is determined to find out and, he adds, he's growing more confident.

"It's passed at least three of the tests," he said. "It's a meteor."

© Darryl Pitt, Macovich Collection, via AP

A Martian meteorite was recovered in December last year near Foumzgit, Morocco.

A Martian meteorite was recovered in December last year near Foumzgit, Morocco.

Washington - Scientists are confirming a recent and rare invasion from Mars: meteorite chunks from the red planet that fell in Morocco last July.

This is only the fifth time scientists have chemically confirmed Martian meteorites that people witnessed falling. The small rock refugees were seen in a fireball in the sky six months ago, but they weren't discovered on the ground in North Africa until the end of December.

Scientists and collectors of meteorites are ecstatic and already the rocks are fetching big bucks because they are among the rarest things on Earth.

A special committee of meteorite experts, which includes some NASA scientists, confirmed the test results Tuesday. They certified that 15 pounds of meteorite recently collected came from Mars. The biggest rock weighs over 2 pounds.

Astronomers think millions of years ago something big smashed into Mars and sent rocks hurtling through the solar system. After a long journey through space, one of those rocks eventually landed here. It plunged into Earth's atmosphere, splitting into smaller pieces and one chunk shattered into shards when it hit the ground.

This is an important and unique hands-on look at Mars for scientists trying to learn about the planet's potential for life. So far, no NASA or Russian spacecraft have returned bits of Mars, so the only Martian samples scientists can examine are those that come here in a meteorite shower.

Most other samples had been on Earth for millions of years - or at the very least decades - which makes them tainted with Earth materials and life. These new rocks, while still likely contaminated because they have been on Earth for months, are still more pure and better to study.

The last time a Martian meteorite fell and was found fresh was in 1962. All the Martian rocks on Earth add up to less than 240 pounds.

The new samples were scooped up by dealers from those who found them. Even before the official certification, scientists at NASA, museums and universities scrambled to buy or trade these meteorites.

"It's a free sample from Mars, that's what these are, except you have to pay the dealers for it," said University of Alberta meteorite expert Chris Herd, who heads the committee that certified the discovery.

He's already bought a chunk of meteorite and said he was thrilled just to hold it, calling the rock "really spectacular."

One of the key decisions the scientists made Tuesday was to officially connect these rocks to the July fiery plunge witnessed by people and captured on video. The announcement and naming of these meteorites - called Tissint - came from the International Society for Meteoritics and Planetary Science, which is the official group of 950 scientists that confirms and names meteorites.

Meteorite dealer Darryl Pitt, who sold a chunk to Herd, said he charges from $11,000 to $22,500 an ounce and he's sold most of his already. At that price, the new Martian rock costs about 10 times more per ounce than gold.

A sun-watching spacecraft has for the first time tracked a comet's path all the way into the solar atmosphere

As dramatic exits go, it's on par with Major T. J. "King" Kong riding a falling nuclear bomb like a rodeo bull at the end of Dr. Strangelove. A NASA spacecraft has documented a comet's demise as it plunged toward the sun at 600 kilometers per second, broke apart and vaporized inside the solar atmosphere.

The comet, known as C/2011 N3 (SOHO), met its fiery fate on July 6. The object's official name designates that it was discovered in early July 2011 by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft. Many comets meet a similar end, but astronomers and solar physicists have never been able to track a comet's trajectory all the way into the depths of the solar corona, the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere.

With the help of another spacecraft - NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which was launched in 2010 - a group of scientists were able to witness the final minutes of the comet's existence. The observations of C/2011 N3 as it broke apart allowed the researchers to estimate the comet's mass and the size of its nucleus; similar events in the future may provide clues about the origins of comets as well as probe conditions near the sun that are otherwise difficult to explore. The team of researchers published their findings in the January 20 issue of Science.

SOHO has discovered more than 2,000 comets near the sun, most of them thanks to the help of unpaid amateur astronomers who comb through imagery from the spacecraft. Most of the sun-grazing comets, like C/2011 N3, belong to the Kreutz family, which is thought to have originated from a single progenitor that broke apart within the past few thousand years. The smallest of these comets are destroyed by the sun before they draw too close, so C/2011 N3 was rather sizable for a Kreutz-family comet, with a nucleus 10 to 50 meters across.

"It must have been on the large side," says lead study author Carolus Schrijver, a solar physicist at the Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif. The comet's size contributed not only to its survival deep into the solar atmosphere but also to its receiving close scrutiny during the sunward plunge. "This was noted as a particularly bright one," Schrijver says. "That morning as it was approaching the sun I said, 'Well, let's see if we can see it.'"

An atmospheric imaging camera on SDO was indeed able to track the inbound comet, watching it bear down on the sun in an ultraviolet streak that lasted about 20 minutes before it disappeared. By that time the comet was only about 100,000 kilometers above the solar surface and had broken into a number of fragments, further hastening its vaporization.

"The temperatures [at that point] are so high that things are evaporating," says astronomer Matthew Knight of Lowell Observatory and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who did not contribute to the new study. "Not just gases and ices, but heavy elements."

The comet's total obliteration in the solar atmosphere let Schrijver and his colleagues estimate how much material was lost in the process. "Because it vanished, we could actually measure its mass," Schrijver says. The researchers estimate that the comet may have shed as much as 60 million kilograms of material in its plunge - about the mass of the Titanic. But the comet's composition is less clear. "We're still trying to understand what was glowing," he says. The imager used to track C/2011 N3 is most sensitive to iron, but Schrijver notes that the glow could also have been produced by carbon or oxygen.

As dramatic exits go, it's on par with Major T. J. "King" Kong riding a falling nuclear bomb like a rodeo bull at the end of Dr. Strangelove. A NASA spacecraft has documented a comet's demise as it plunged toward the sun at 600 kilometers per second, broke apart and vaporized inside the solar atmosphere.

The comet, known as C/2011 N3 (SOHO), met its fiery fate on July 6. The object's official name designates that it was discovered in early July 2011 by the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft. Many comets meet a similar end, but astronomers and solar physicists have never been able to track a comet's trajectory all the way into the depths of the solar corona, the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere.

With the help of another spacecraft - NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which was launched in 2010 - a group of scientists were able to witness the final minutes of the comet's existence. The observations of C/2011 N3 as it broke apart allowed the researchers to estimate the comet's mass and the size of its nucleus; similar events in the future may provide clues about the origins of comets as well as probe conditions near the sun that are otherwise difficult to explore. The team of researchers published their findings in the January 20 issue of Science.

SOHO has discovered more than 2,000 comets near the sun, most of them thanks to the help of unpaid amateur astronomers who comb through imagery from the spacecraft. Most of the sun-grazing comets, like C/2011 N3, belong to the Kreutz family, which is thought to have originated from a single progenitor that broke apart within the past few thousand years. The smallest of these comets are destroyed by the sun before they draw too close, so C/2011 N3 was rather sizable for a Kreutz-family comet, with a nucleus 10 to 50 meters across.

"It must have been on the large side," says lead study author Carolus Schrijver, a solar physicist at the Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, Calif. The comet's size contributed not only to its survival deep into the solar atmosphere but also to its receiving close scrutiny during the sunward plunge. "This was noted as a particularly bright one," Schrijver says. "That morning as it was approaching the sun I said, 'Well, let's see if we can see it.'"

An atmospheric imaging camera on SDO was indeed able to track the inbound comet, watching it bear down on the sun in an ultraviolet streak that lasted about 20 minutes before it disappeared. By that time the comet was only about 100,000 kilometers above the solar surface and had broken into a number of fragments, further hastening its vaporization.

"The temperatures [at that point] are so high that things are evaporating," says astronomer Matthew Knight of Lowell Observatory and the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who did not contribute to the new study. "Not just gases and ices, but heavy elements."

The comet's total obliteration in the solar atmosphere let Schrijver and his colleagues estimate how much material was lost in the process. "Because it vanished, we could actually measure its mass," Schrijver says. The researchers estimate that the comet may have shed as much as 60 million kilograms of material in its plunge - about the mass of the Titanic. But the comet's composition is less clear. "We're still trying to understand what was glowing," he says. The imager used to track C/2011 N3 is most sensitive to iron, but Schrijver notes that the glow could also have been produced by carbon or oxygen.

And skywatchers were out in droves when the Quadrantid meteor shower put on its annual display earlier this month. Last weekend, the Russian Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, the country's 19th attempt to reach Mars, plunged back to Earth amid much speculation about the effects of its toxic fuel.

Near Earth Objects

We're getting used to the idea we're under continual bombardment from the heavens. But as well as objects from Earth orbit, there are some more sinister things to worry about: the nearly 8,000 identified Near Earth Objects (NEOs), asteroids, comets and meteoroids, whose orbits bring them close enough to Earth for collision to be a real risk. In November last year, the asteroid 2005 YU55 missed the Earth by a mere 300,000km.

So what are we doing about this? At a panel convened last week in Adelaide by the International Space University's Southern Hemisphere Summer Space Program, experts noted that our knowledge about what's "out there" has increased exponentially in recent decades. We've got a pretty good idea of what is roaming around in the Near Earth environment.

But as they also pointed out, very little is actively being done in the Southern Hemisphere to track and prepare for events such as re-entries.

It wasn't always this way: until 1996, the Australian government funded a Spaceguard program, which was responsible for identifying one-third of all catalogued NEOs - a very impressive track record. There are currently calls to revive Spaceguard activities, bringing Australia more into line with international efforts. (And in the meantime, it looks as if Australia will participate in talks with the US and Europe to help address the space junk issue.)

Australia is indeed very well placed, in terms of its location, size, expertise and availability of radio-quiet areas, to play an important role in observing and tracking both natural and human-manufactured objects in space. It's also one of the few countries that has direct experience in what happens when a spacecraft makes an uncontrolled re-entry over land.

In 1979, Skylab, one of the largest spacecraft ever launched at that time, fell out of the sky in flaming fragments over Western Australia. No-one was hurt and there was no property damage, although the Shire of Esperance famously fined the US State Department $400 for littering. (The fine was finally paid in 2009 by public donations).

Hit and miss

The first thing to note is that you would have to be very unlucky indeed to have a piece of space junk fall on you. It's only happened once that we know of. According to the Centre for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies (CORDS), Lottie Williams of Oklahoma was hit by a small piece of a Delta II rocket as she was taking a walk one day in 1996. She was unharmed. Similarly, there are no accounts of people being injured by meteorites. There's just so much ocean, desert and ice - and this is usually where the stuff lands.

Accounts of Skylab's re-entry, however, can be used to derive some indications about what to expect. Sonic booms typically accompany objects falling at high speed through the upper atmosphere. As with fireworks, these loud noises can upset domestic pets and livestock. Take the same precautions as you would for your pets on New Year's Eve; there is plenty of information about this online.

Falling meteorites have frequently been blamed for causing fires, and this was also a concern for people in the debris footprint of Skylab. Having an up-to-date fire plan and managing the local risk around your house in terms of available fuel are the best way to prepare for this.

If spacecraft fragments fall near you, don't rush to collect them. For a start, there may be toxic fuel residues or metals such as beryllium, or radioactive material from power sources and onboard experiments. The most common spacecraft components to survive re-entry are spherical titanium pressure vessels.

Usually regarded as an inert metal, titanium is now thought to have dangerous corrosion products. There are no recorded instances of people falling ill from contact with space junk, but there's no point taking the risk.

As appealing as the idea of having a personal souvenir of space is, this is not technically junk. Under the terms of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the fragments belong to the country which launched the spacecraft. So don't collect fragments and sell them on eBay - as people may well have done if the internet existed in 1979. (But, if you are really keen, you can still buy tiny pieces of Skylab encased in resin with an authentification certificate today). The pieces can be used to analyse the re-entry event, and perhaps what went wrong with the spacecraft.

If you or your property have been damaged by the spacecraft, you may be entitled to compensation. It will be the responsibility of the appropriate government agency to negotiate what happens next. For most countries, this will be the national space agency. The closest Australia has at the moment is the Space Policy Unit based in Canberra.

Next time you hear that a spacecraft might fall on Australia, don't be too alarmed. Keep an eye on the predictions, bring your kittens inside, and rejoice in the fact that there is one less object clogging up Earth's orbit. If you are concerned about NEOs, join those lobbying for the reinstatement of Spaceguard.

It's not all doom and gloom. The stuff that falls from space reminds us we are part of the cosmos too.

Alice Gorman is a faculty member of the International Space University Southern Hemisphere Summer Space Program.

NEOShield is a new international project that will assess the threat posed by Near Earth Objects (NEO) and look at the best possible solutions for dealing with a big asteroid or comet on a collision path with our planet.

The effort is being led from the German space agency's (DLR) Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin, and had its kick-off meeting this week.

It will draw on expertise from across Europe, Russia and the US.

It's a major EU-funded initiative that will pull together all the latest science, initiate a fair few laboratory experiments and new modelling work, and then try to come to some definitive positions.

Industrial partners, which include the German, British and French divisions of the big Astrium space company, will consider the engineering architecture required to deflect one of these bodies out of our path.

Should we kick it, try to tug it, or even blast it off its trajectory?

"We're going to collate all the scientific information with a view to mitigation," explains project leader Prof Alan Harris at DLR.

"What do you need to know about an asteroid in order to be able to change its course - to deflect it from a catastrophic course with the Earth?"

It's likely that NEOShield will, at the end of its three-and-a-half-year study period, propose to the politicians that they launch a mission to demonstrate the necessary technology.

The NEO threat may seem rather distant, but the geological and observational records tell us it is real.

On average, an object about the size of car will enter the Earth's atmosphere once a year, producing a spectacular fireball in the sky.

About every 2,000 years or so, an object the size of a football field will impact the Earth, causing significant local damage.

And then, every few million years, a rock turns up that has a girth measured in kilometres. An impact from one of these will produce global effects.

The latest estimates indicate that we've probably found a little over 90% of the true monsters out there and none look like they'll hit us.

It is that second category that merits further investigation.

Data from Nasa's Wise telescope suggests there are likely to be about 19,500 NEOs in the 100-1,000m size range, and the vast majority of these have yet to be identified and tracked.

New telescopes are coming that will significantly improve detection success. In the meantime, the prudent course would be to develop a strategy for the inevitable.

The strongest mitigation candidates currently would appear to be:

Kinetic impactor: This mission might look like Nasa's Deep Impact mission of 2005, or the Don Quijote mission that Europe designed but never launched. It involves perhaps a shepherding spacecraft releasing an impactor to strike the big rock or comet. This gentle nudge, depending when and how it's done, could change the velocity of the rock ever so slightly to make it arrive "at the crossroads" sufficiently early or late to miss Earth.

"The amount of debris, or ejecta, produced in the impact would affect the momentum of the NEO," says Prof Harris.

"Of course, that will depend on what sort of asteroid it is - its physical characteristics. What's its surface like; how porous or dense it is? This is really something you would want to test with a demonstration mission."

"Gravity tractor": This involves positioning a spacecraft close to a target object and using long-lived ion thrusters to maintain the separation between the two. Because of gravitational attraction between the spacecraft and the NEO, it is possible to pull the asteroid or comet off its trajectory. "It's like using gravity as a tow-rope," says Prof Harris. "It's not straightforward of course. Can you be sure those thrusters will keep working for the time they're needed - a decade or more? Do you have confidence that the spacecraft can look after itself autonomously all that time? These are the sorts of technical problems we will look at."

In both scenarios, the effects are small, but if initiated years - even decades - in advance should prove effective enough.

What we've learnt about asteroids, however, is that they are not all the same. Different rocks are likely to need different approaches.

One method often discussed but about which there is great uncertainty is "blast deflection" - the idea that you would detonate a nuclear device close to, or on the surface of (even buried under the surface), an incoming rock.

The Russian members of the NEOShield consortium will take a close look at the option.

At present, I detect a lot of scepticism out there about this approach. Delivering the device to just the right place would prove very difficult, and the outcomes, depending on the composition and construction of the NEO, would be very hard to predict. But some better numbers than we have currently are required and TsNIIMash, the engineering arm of the Russian space agency (Roscosmos), will gather all the available data.

"What we want to do is take a comprehensive view, to try to draw everything we know together, with the right expertise so that this thing has momentum," commented Dr Ralph Cordey, from Astrium UK.

"We will look at the spectrum of techniques, trying to see which ones might be applicable in different cases. And then taking it to a level where we do some detailed design work on a possible mission to demonstrate one or more of these techniques."

And Prof Harris added: "At the end of this, we want to be able to say to the space agencies 'if you're interested in asteroid mitigation, this is what we think. We have six countries represented in our consortium and we're all agreed this is the way to go'.

"The politicians would then have everything on a plate. All they have to do is decide whether or not to execute the mission."

The effort is being led from the German space agency's (DLR) Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin, and had its kick-off meeting this week.

It will draw on expertise from across Europe, Russia and the US.

It's a major EU-funded initiative that will pull together all the latest science, initiate a fair few laboratory experiments and new modelling work, and then try to come to some definitive positions.

Industrial partners, which include the German, British and French divisions of the big Astrium space company, will consider the engineering architecture required to deflect one of these bodies out of our path.

Should we kick it, try to tug it, or even blast it off its trajectory?

"We're going to collate all the scientific information with a view to mitigation," explains project leader Prof Alan Harris at DLR.

"What do you need to know about an asteroid in order to be able to change its course - to deflect it from a catastrophic course with the Earth?"

It's likely that NEOShield will, at the end of its three-and-a-half-year study period, propose to the politicians that they launch a mission to demonstrate the necessary technology.

The NEO threat may seem rather distant, but the geological and observational records tell us it is real.

On average, an object about the size of car will enter the Earth's atmosphere once a year, producing a spectacular fireball in the sky.

About every 2,000 years or so, an object the size of a football field will impact the Earth, causing significant local damage.

And then, every few million years, a rock turns up that has a girth measured in kilometres. An impact from one of these will produce global effects.

The latest estimates indicate that we've probably found a little over 90% of the true monsters out there and none look like they'll hit us.