Larry O'Hanlon

Discovery News

Mon, 31 Mar 2008 04:51 EDT

A new report of tiny beads of meteor impact glass strewn high in Antarctica's Transantarctic Mountains may expand a debris field to a tenth of Earth's surface -- despite no sign of the crater which spewed out the molten rock 800,000 years ago.

The accidental discovery of the glass "microtektites" in the high mountains of Antarctica extends what's called the Australasian tektite strewn field south by nearly 2,000 miles (3,000 kilometers).

The microtektites were found while a team of researchers were searching the exposed rocks atop the Transantarctic Frontier Mountain for more pieces of an unrelated meteorite that disintegrated in the skies there long ago.

"The gradiometer kept on beeping at every fracture of the granitic bedrock surface," recalled Italian researcher Luigi Folco of the Museo Nazionale dell'Antartide, Università di Siena and the Italian Programma Nazionale delle Ricerche in Antartide.

A magnetic gradiometer detects minute changes in magnetic fields caused by rocks containing magnetic minerals. The most likely cause for the beeping was magnetic minerals in volcanic ash from one of the relatively recent volcanoes in the region.

"When we get back to the lab, to our great surprise, we found thousands of micrometeorite and cosmic spherules thus explaining the magnetic signal," Folco told Discovery News.

But they also found glass spheres 0.5 millimeter in diameter with a pale-yellow color, which is unusual for glassy cosmic spherules, which are the debris of meteors melting in Earth's atmosphere.

The chemical composition of the yellow spheres revealed them to be Earth rocks. That meant there was only one likely way they could have been created -- in the heat of an impact, which flung melted rock into space and then rained back down, cooling and solidifying into spheres while in free fall.

The discovery was written up and reported in the April issue of the journal Geology.

The analysis of the microtektites revealed they are similar enough in appearance, composition and age to represent the edges of the Australasian strewnfield, said Folco. That strewnfield already had been found to extend from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific.

"It's a pretty big strewn field," said tektite pioneer and professor emeritus Bill Glass of the University of Delaware.

Larger tektites from the impact have been found all over Australia and smaller microtektites have been extracted from the bottom of the Indian Ocean, he told Discovery News. But this is the first good evidence that the debris might have been flung even further, he explained.

"You'd think that something that big would be easy to find," said Glass. "It's a real puzzle."

The most likely location of the hidden crater is somewhere in Indochina, said Glass. One possibility is that the meteor struck down on what is the sea floor today. But 800,000 years ago, an ice age would have lowered the sea level and exposed the seafloor. Since then it could have been buried by marine sediments.

Shooting Star Shower Spotted on Mars

Dave Mosher

Space.com

Tue, 01 Apr 2008 20:42 EDT

A shower of shooting stars has been recorded by instruments on Mars for the first time, astronomers say.

Meteors have been spotted before by the Mars rovers, but no device has ever detected a full shower until now.

United Kingdom astronomers predicted the event by tracking a comet's path near Mars, then comparing their forecast with Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) satellite data of the red planet's ionosphere - the upper reaches of atmosphere teeming with charged particles.

"Just as we can predict meteor outbursts at Earth, such as the Leonids [shower that occurs every November], we can also predict when meteor showers are going to occur at Mars and Venus," said Apostolos Christou, an astronomer at the U.K.'s Armagh Observatory who helped predict the martian meteoric event.

Christou is set to present findings about the meteor-showering pass of comet 79P/du Toit-Hartley at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting in Belfast on April 2.

Meteor central

Just as on Earth, meteor showers on Mars can occur when a planet passes through the dusty trail of a comet.

There are no conventional photos of the meteors in the new findings, but studying the brightness and length of meteor streaks in optical and radio data, Christou said, can help determine the age, size and composition of a comet's core.

Scientists think four times as many comets dust Mars with their tails compared to our home planet, as a high proportion of comets hang out near Jupiter - the red planet's next-closest neighbor. So there could be many more meteor showers visible from Mars than from Earth.

Some even blame such frequent comet dusting of Mars for the puzzling course change of Mariner 4, the first spacecraft to visit Mars, in the 1960s.

Fuzzy details

Christou said detecting the distant meteor shower wasn't easy.

"We believe that shooting stars should appear at Venus and Mars with a similar brightness to those we see at Earth," he said. "However, as we are not in a position to watch them in the martian sky directly, we have to sift through satellite data to look for evidence of particles burning up in the upper atmosphere."

Christou and his colleagues predicted six meteor showers caused by the intersection of Mars with dust trails from comet 79P/du Toit-Hartley since 1997, which was when the MGS satellite entered orbit.

The team pinpointed meteor streaks indirectly by measuring disturbances in electrical density of Mars' atmosphere with the spacecraft's radio communication system.

Out of the two showers MGS could have recorded - in 2003 or 2005 - Christou and his colleagues found hints of a shower only in data of the 2003 event.

"We don't see anything in the 2005 data because the meteors burned up deeper in the atmosphere," he said, adding that the depth would cover up an electrical signature. "If we are going to get a clear picture of what is going on, we need more optical and ionospheric observations of meteor showers at both the Earth and Mars so we can establish a definitive link between cause and effect."

Bruno Matarazzo Jr.

Salem News

Tue, 01 Apr 2008 09:56 EDT

IPSWICH - A bit of a mystery is lingering over Crane Beach: A

Beverly man wants to know what he saw falling from the sky yesterday

afternoon.

"It definitely was not a UFO," stressed Richard Wilson, an engineer originally from Wales. "It was bloody bizarre."

Wilson was spending the afternoon enjoying the beautiful weather

with his wife and son at Crane Beach. His walk was just ending when

something caught the attention of him and other beachgoers.

Wilson saw two objects fall within 15 minutes of each other. The

first, a rather large piece, fell between Crane Beach and Little Neck

near the Ipswich River.

The second object fell as he and his family were headed for the parking lot.

"We were walking back to our car, crossing over the boardwalk, and

someone ran towards us," Wilson said. "I looked up at the sky and there

were 20 to 30 pieces really high up and they fell on the dunes."

One man managed to pick up the smaller piece but Wilson couldn't get

to him without walking a long way on the dunes. The rest of the pieces

blew away to a swampy area behind the dunes.

The first piece fell at 1:30 p.m. and was much bigger, about 200 to 300 feet long, Wilson estimated.

"There was a plane in the sky doing aerobatics near the sea - this

stuff was higher than that," Wilson said. "It rolled over and (was)

moving like a piece of material, getting blown away."

The first piece to fall caught the attention of many beachgoers, and they stared up at the sky.

While Wilson said many people were captivated by the falling object,

park rangers from The Trustees of the Reservation, which owns the

beach, said no one informed them of any falling objects.

Ipswich police were not notified until about 2 p.m. when a Boston

television station called them about the report, which they heard about

from a viewer.

Police Sgt. Justin Daly said officers from the day shift responded

to the beach to investigate, but no one reported seeing anything.

"After a brief investigation it was determined nothing fell out of the sky," Daly said.

Police in Rowley and Newbury also reported no calls about objects falling from the sky.

Wilson said he may return to Crane Beach to do more of his own investigation and try to locate the smaller fallen pieces.

"It's a mystery," he said.

Staff writer Bruno Matarazzo Jr. can be reached at 978-338-2525 or by e-mailing bmatarazzo@salemnews.com.

Paul Gorman

press.co.nz

Thu, 03 Apr 2008 16:00 EDT

Teenager Andrew Wilkinson captured an apparently fiery object in the Canterbury sky on his digital camera last night.

|

| ©Andrew Wilkinson |

| Teenager Andrew Wilkinson captured this mysterious picture of a fiery trail in the sky above Christchurch. |

Wilkinson, 17, photographed the object, from his Halswell home at 7.27pm.

He said it was too slow to be a meteor or a plane, and wondered if it might be satellite debris in the western sky.

A handful of other observant Cantabrians also spotted the orange ribbon standing out brightly in the dusk.

"I got the camera and took a photo. It was moving extremely slowly,

so I thought it might have been a plane for a minute. The front looked

like a fireball.

"I didn't hear any noise. It looks like it might have been extremely high up, given the speed it was moving," he said.

Police southern communications shift supervisor Trevor Cross said he

received one phone call about the phenomenon. A policeman at Oxford

also saw it and thought it might be a vapour trail.

The superintendent of the University of Canterbury's Mount John

Observatory at Tekapo, Alan Gilmore , said his "immediate reaction" was

it was a plane.

"The slowness would be due to the plane's movement. I assume from

the contrail's angle that it is a plane heading for Australia," Gilmore

said. "The trail doesn't look at all like a meteor or space-debris

trail."

P. Jenniskens, Carl Sagan Center, SETI Institute

Space.com

Thu, 03 Apr 2008 13:04 EDT

Each generation seems to get a chance, or two, to see a

mind-boggling display of shooting stars one night. The most spectacular

displays in my memory are the 1999 and 2001 Leonid storms. Before my

time, observers swore by the 1966 Leonids, and could not stop talking

about the spectacular 1933 and 1946 Draconid storms. Those were not

quite as intense as the Leonids, but the Draconids moved so slowly that

several were seen gliding across the sky at the same time.

In the 19th century, the most spectacular storms were the 1872 and

1885 Andromedids, which were almost as strong as the Draconids and also

very slow moving. At the time, Chinese astronomers wrote: "shooting

stars fell like rain." From the counts of meteors in the west, we now

estimate that rates peaked around two per second.

Some years earlier, in 1846, a comet

called 3D/Biela had been observed to break into at least two pieces.

The pieces had drifted further apart in 1852. Based on the rate of that

drift, the moment of breakup is thought to have been in either 1842 or

early 1843, when the comet was far from the sun, near Jupiter's orbit.

Because of their phenomenal intensity, the Andromedid storms were

believed to be caused by Earth traveling through the debris created

during that breakup.

So, did we pass through the breakup debris of comet 3D/Biela?

Astronomer Jeremie Vaubaillon, now at Caltech, and I decided to

investigate. We calculated where the debris from 1842/43 would have

ended up in the comet orbit

and discovered that a breakup far from the sun does not disperse dust

easily. The dust tends to keep the same orbital period, returning back

at the same time. The cloud of dust tends to hang around the position

of the comet, only gradually lagging the comet as a whole due to the

push of solar radiation.

We concluded that Earth has never encountered the debris created

during the 1842/1843 breakup! So what caused the Andromedid meteor

storms? Upon further reflection, we calculated that Earth had passed

through the dust trails that were generated when the two fragments came

back towards the sun in 1846 and 1852. Ejection close to the sun

results in higher ejection speeds and thus a relatively large variation

of orbital periods. After one orbit, some dust returns early, other

dust late, and thus all dust spreads out along the comet orbit much

more quickly. We found that the planets happened to steer those new

dust trails into Earth's path every time when observers on the ground

noticed unusual Andromedid rates in later years.

What if Earth would have crossed the dense cloud of debris of the

broken comet shortly after 1843? The resulting meteor storm would have

been a hundred times more intense, if not more. The impressive storms

of 1872 and 1885 were caused by a tiny bit of dust, we estimate 30

times less than what came off during the initial breakup. Moreover,

that dust had spread out quite a bit. Just imagine what could have

been. We appear to have missed out on a truly spectacular sight.

Then again, the next generation may be in for a surprise. The

Andromedids have moved on and now pass far from Earth's orbit, but

other comets continue to break and create new meteoroid

streams. One date to keep in mind is May 31, 2022, when Earth will pass

very close to (but perhaps will just miss) debris created during the

1995 breakup of comet 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3. And there may be

others; we don't know yet what dormant comet nuclei may be out there

that could break any time now.

Read more about these calculations in the paper "3D/Biela and the

Andromedids: Fragmenting versus sublimating comets," by P. Jenniskens

and J. Vaubaillon (Astronomical Journal, 134, 1037-1045).

7Days

Fri, 04 Apr 2008 12:14 EDT

An eagle-eyed 7DAYS reader believes this picture (below) could hold

the answer to the mysterious fate of thousands of dead fish that were

washed up on a beach in Jumeirah. Chenine Groenewald pictured what she

thought was a meteorite falling from the sky on Monday.

|

| ©Chenine Groenewald |

It coincides with the unusual sight of thousands of small silver

fish found dead on the beach on the same day. Authorities still do not

know what killed the fish, which locals were seen gathering up for

food. But Groenewald believes the meteorite could have fallen into the

sea, killing the marine life. "I'm not sure if it is related to the

fish being washed up dead, but I saw something falling from the sky on

Monday evening, in that direction, which I would assume is a

meteorite," she said.

The MET Office, however, rubbished the idea that the picture is of a

meteorite. "We are not astronomers, but it looks like a contrail from

an airplane," a spokesman said. But a defiant Groenewald responded: "It

was coming down quite quickly and I didn't see any plane nearby - I've

never seen anything like it."

TV3 New Zealand

Fri, 04 Apr 2008 13:00 EDT

|

| ©Andrew Corner |

| Jet vapour trail or something else? |

A bright shining light that streaked across the Canterbury sky at

sunset earlier this week has now been identified by the experts.

A deer hunter on a mountain top near Arthur's Pass caught the object

on his video camera, allowing astronomers to take a look at it as well.

Andrew Corner did not expect to see an unidentified flying object

flying through the sky as he hunted deer in the back of beyond.

Corner and his friends discussed the fireball burning across the

sky, wondering whether it was a plane or space debris burning up. They

say they did not discuss the possibility of aliens.

Craig Garner of Stardome Observatory says: "Looking at this particular picture I would say it's definitely a jet vapour trail."

The hunters failed to get any deer on the hunt but say the fireball sighting made up for it.

Chaz Firestone

The Brown Daily Herald

Fri, 04 Apr 2008 06:36 EDT

Last September, something strange landed near the rural Peruvian village of Carancas. Two months later, so did Peter Schultz.

One was an extraterrestrial fireball that struck the Earth at 10,000

miles per hour, formed a bubbling crater nearly 50 feet wide and

afflicted local villagers and livestock with a mysterious illness. The

other is the Brown geologist who may have figured out why.

|

| ©Brown Daily Herald |

| Professor of Geological Sciences Peter Schultz |

The fiery mass shot across the morning sky bursting and crackling

like fireworks, villagers said after the Sept. 15 impact. An explosive

crash tossed nearby locals to the ground, shattered windows one

kilometer away and kicked up a massive dust cloud, covering one man

from head to toe in a fine white powder. Many thought the streaking

fireball - brighter than the sun, by some accounts - was an aerial

attack from neighboring Chile.

Curious shepherds and farmers approached the crash site to find a

smoking crater reminiscent of a Hollywood film, laden with rocks and

stirring with bubbling water that emitted a foul vapor. But curiosity

turned to fear when unexplained symptoms began to crop up in Carancas:

headaches, vomiting and skin lesions struck more than 150 villagers,

Peru's Ministry of Health stated days later. Locals reported that their

animals lost their appetites and bled from their noses. Children were

restless and cried through the night.

But according to Schultz, the professor of geological sciences who

visited the site last December, the true mystery in Carancas is how any

of this happened in the first place.

Sophisticated theory and conventional wisdom have long agreed that

most meteors break into fragments and fizzle out before they can reach

the Earth's surface. Even those large and durable enough to make it

through the atmosphere hit the ground as ghosts of their former selves,

"plopping out of the sky and forming a bullet hole in the Earth,"

Schultz said. "This meteor crashed into the Earth at three kilometers

per second, exploded and buried itself into the ground."

Last month, Schultz delivered a highly anticipated lecture at the

39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in League City, Texas. And

if he's right, the bold theory he proposed there may shake loose a "gut

response" entrenched within the geological, physical and astronomical

sciences: "Carancas simply should not have happened."

A Web of speculation

The handful of shepherds who happened to lead their Alpaca herds

near the arroyo that day may have been the first humans ever to witness

an explosive meteor impact. But the rest of the world quickly got its

chance, if vicariously, through a flurry of activity in the blogosphere.

Hundreds of scientists, journalists and captivated amateurs weighed

in on the bizarre events as they unfolded, offering scores of pet

theories and radically revising them as more information streamed in

from Peru.

Pravda, a Russian online newspaper born out of a print version run

by the country's former Communist Party, ran the headline "American spy

satellite downed in Peru as U.S. nuclear attack on Iran thwarted" five

days after the impact. The story attributes the villagers' illness to

radiation poisoning from the satellite's plutonium power generator.

Other proposed explanations were less sensational. Nevadan wildlife

biologist and amateur geologist David Syzdek wrote a Sept. 18 blog post

titled "Meteorite strike in Peru gassing villagers? Maybe not." In it,

he proposed that a mud volcano producing toxic gases was responsible

for both the illness and the crater.

"The Andes are very active geologically so I think there is a good

possibility that this crater was caused by an outburst of geothermal

activity," he wrote.

As for the blinding light shooting across the sky, Syzdek chalked it up to coincidence.

"Fireballs are quite common," he wrote. "One possible scenario is

that the people who saw the fireball just happened on a recently formed

mud volcano while they were out looking for the fireball impact site."

Though Pravda and Syzdek drew radically different conclusions from

the reports, what they shared with each other, many bloggers and even

some scientists was a healthy skepticism about reports coming out of

Peru. Pravda and Syzdek both pointed out in their posts that an

explosion powerful enough to create such a large crater would be

equivalent to 1,000 tons of TNT, or a tactical nuclear strike.

"When I first saw the news reports, they just didn't seem right,"

Syzdek later said in an interview. "Explosive impacts like this just

don't happen."

'A hyperspeed curveball'

Gonzalo Tancredi, a Uruguayan astronomer who collaborated with

Schultz in Carancas, said initial reports of the impact confounded

amateurs and Ph.D.s alike. Bewildered scientists even entertained the

possibility of a hoax as rumors floated around the scientific community.

"At the beginning, there were some doubts about what really happened

there," Tancredi said. "We thought maybe it was a meteor fall or maybe

it was something else, even something fake."

But when Tancredi visited Carancas a few weeks later, what he

observed silenced the conspiracies and pointed unequivocally to one

conclusion.

Tancredi interviewed locals, who reported a large mushroom cloud

that formed over the crater and compression waves that knocked

villagers to the ground. He also found pieces of soil and rock that had

been launched over three football fields from the crater - one piece

even pierced the roof of a barn 100 meters away. Combined with analyses

of infrasound detectors and the patterns of crater "ejecta," the

evidence pointed to a genuine and very powerful meteorite impact.

But the question that remained on everyone's mind was how the meteor

got there at all - a scientific riddle that was made even more

challenging by Michael Farmer.

Farmer is a controversial figure in the geological community. He is

a meteorite hunter, a poacher of alien rocks who travels to impact

sites around the world - usually the "bullet hole in the Earth" type

mentioned by Schultz - and collects whatever he can find, often

brushing up against authorities and other hunters. Meteorite hunting is

Farmer's full-time job; he profits from selling what he finds.

Farmer, who said he is "totally self-taught" when it comes to

meteors, said he was as skeptical as the rest when he first heard the

reports coming out of Peru while on hunt in Spain. But 16 days later,

he and his partners found themselves staring into the Carancas impact

crater, the first Americans on the scene - and they stumbled on an

extraterrestrial gold mine.

"We got there and just started picking up pieces off the ground,"

Farmer said. "The entire ground was white, just white powder which was

all meteor."

Farmer and his team eventually accumulated 10 kilograms of small

meteorite fragments and sold them to private collectors and

universities for an astronomical $100 per gram.

But despite his rocky past with the geological community, Farmer and

his expensive fragments made a priceless contribution to scientists.

Within minutes of arriving on the scene, Farmer discovered that the

Carancas meteorite was a chondrite, or stony meteorite, as opposed to

an iron meteorite.

Though far more common than iron meteorites, chondrites are highly

vulnerable to ablation - the cracking, eroding and even exploding that

occurs when a meteor enters the atmosphere and undergoes extreme

changes in temperature and pressure. As a result, chondrites are far

less likely than the more durable iron meteorites to make it to the

Earth's surface in large pieces - which makes the Carancas meteorite

all the more baffling.

"For a while, the only information we were getting was from Farmer's

Web site," Schultz said. "This was not the type of object you'd expect

to get through the atmosphere in a tight clump."

With most pieces of the geological puzzle on the table, the stage

was set for Schultz to visit the site for himself. But when he arrived

there in December with a Brown graduate student, Tancredi and Peruvian

astrophysicist Jose Ishitsuka, a budding geologist actually made the

crucial discovery. Scott Harris GS said he collected some soil samples

"initially out of curiosity" to look for evidence of shock deformation,

which occurs when an object rapidly decelerates in cases like impacts

or explosions. When Harris looked at the material under a microscope,

he found tiny mineral grains that had turned into glass because of heat

and massive shock forces, indicating a very high-speed impact. Here was

yet another mystifying piece of evidence.

"At the minimum," Harris said, "this would support a velocity of

three kilometers per second - a real high-velocity explosion instead of

just a plop in the ground."

By this time, more reputable scientific theories of the impact had

supplanted the initial speculation, the most popular of which came from

a group in Germany and Russia. They proposed that the meteor entered

the Earth's atmosphere at a very shallow angle, allowing it to reach

the surface gradually and avoid a sudden increase in pressure - "the

difference between diving in and doing a belly flop," Schultz said.

But their theory's relatively low impact velocity of 180 meters per

second, or about 400 miles per hour, was consistent with every piece of

evidence but Harris', which pointed to a velocity of about 10,000 miles

per hour at impact.

"This was nature's way of throwing us a curveball," Schultz said. "A hyperspeed curveball."

Changing shape, changing theory

Back home in Providence, Schultz was now faced with the task of

fitting the puzzle pieces together into a cohesive theory. And to do

it, he looked to Earth's closest planetary neighbor, Venus.

"Our models make predictions about what kind of objects can make it

to the surface at what velocity, and the Carancas meteor isn't usually

one of them," Schultz said. "But Venus has a much denser atmosphere and

we still find craters on its surface. How did they get there? I think

it might be the same thing here."

To explain the alternative theory he developed, Schultz compared a typical meteor's descent to a waterskier behind a boat.

"Normally when you're on the outside of the wake, you're pushed out

further," Schultz said. "From my experience looking at Venus, I

realized that there was a certain condition where the waterskier will

stay inside the wake, and actually get pushed inward."

At last month's Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Schultz

proposed that the meteor did break up into pieces, but shock waves

created by the speeding mass may have kept them close together. And

since the meteor descended as a clump of fragments instead of one large

piece, it reshaped itself along the way to become more aerodynamic,

like a football or a javelin cutting through the air instead of a

poorly shaped hunk of rock.

"It's like having a Volkswagen turn into a Ford Taurus," Schultz

said, adding that this sort of reshaping is well known to geologists

who study islands and land-water interaction. "If you put a big pile of

dirt in a stream, that mound will eventually turn into a teardrop

shape. It's trying to minimize the friction."

Tancredi, who co-authored the paper with Schultz, Harris and

Ishitsuka, said Schultz's theory is gaining popularity but is still

being debated, even among the group that proposed it.

"This is the hot question right now," he said. "We still have to demonstrate that this phenomenon is possible."

In the meantime, another hot question had remained without a

definitive answer - the etiology of the strange illness that afflicted

the people of Carancas. But the group may solve that mystery, too.

Schultz, Harris and Tancredi all dismissed the possibility of the

meteorite emitting harmful gases that would sicken villagers. Instead,

they proposed a simpler cause: the power of the mind.

The meteorite impact sent out a powerful compression wave that

knocked nearby villagers and animals to the ground and injected the

soil with air, which later bubbled up through the crater. Shepherds and

cattle may also have breathed in the thick dust thrown up by the crash

and smelled the sulfurous gases produced as water reacted with iron

sulfide in the meteor.

But what the group thinks later spread through the town was not disease, but panic.

"We think it was probably more of a psychological response," Harris

said, adding that commonplace symptoms like headaches and nausea could

easily have been caused by the disorienting impact and then mirrored by

frightened villagers.

Harris also admitted the possibility of the meteorite releasing

arsenic deposits, which are known to exist in Peru, but said it would

be very unlikely for those gases to have caused the illness.

"In order to really get arsenic poisoning, you'd need high

concentrations," he said. "You'd have to be there inhaling the vapor

filled with the stuff right after the meteorite hit."

Poisonous or not, the Carancas meteorite could have important

implications for public safety. Tancredi said there's no reason an

impact like this couldn't happen in a major city, wiping out a few city

blocks. He also pointed out that today's most advanced meteor detectors

aren't nearly powerful enough to detect an object as small as the

Carancas meteorite.

"Near-Earth detectors detect objects that could create a global

catastrophe, something maybe a kilometer across," he said. "We don't

have any kind of technology that could detect this object before

reaching the atmosphere, so it will not be possible to know when and

where one of these objects could strike again."

But Schultz said the most important lesson to learn from Carancas is

that the foundation of good science is hard empirical evidence, even -

and especially - when it contradicts established principle.

"We tried to understand what the rocks told us rather than looking at the theory," he said. "Nature trumps theory, every time."

Kunio M. Sayanagi

ars technica

Fri, 04 Apr 2008 14:12 EDT

By now, we have all heard about a handful of asteroids that are

big enough to level a city or two and have a small but non-negligible

chance of hitting Earth. Should we find one heading straight at Earth,

what can we do about it, if anything at all?

That is the question addressed by Carusi and colleagues in a study published in the April issue of Icarus,

a leading international journal in the planetary sciences. They

conducted case studies of two near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) known as

99942 Apophis and 2004 VD17, whose initial orbit estimates indicated

measurable probabilities of hitting Earth in 2036 and 2102,

respectively. Although refinements to their orbital calculations

through intensive follow-up observations have substantially lowered

their chances of collisions with Earth, the authors treated the

asteroids' initial orbital estimates as full-blown drills to study how

such asteroids can be deflected, and to build realistic strategies to

prepare ourselves for such events.

The report presents computer simulations that calculate the minimum

orbital velocity change we must impart on the asteroids to deflect them

away from Earth. A larger velocity change requires a stronger force,

and thus imposes a greater technological and financial challenge. To

make the exercise realistic, the authors considered performing their

deflection maneuvers only when the asteroids cross the orbit of Earth -

as the asteroids under consideration are NEAs, they have repeated Earth

orbit crossings leading up to the predicted impact dates.

As expected, in general, the authors' calculations show that greater

speed changes are needed as the hypothesized impact date comes closer.

However, a careful examination also reveals that there are windows of

opportunity in which deflection becomes considerably easier largely due

to the relative orbital geometry of the asteroids and Earth. For

example, in the case of 99942 Apophis, estimated to be a 400 meter

chunk of rock, an impactor with 300 kg mass can deflect the asteroid to

safety with a carefully angled interception on January 27th, 2020,

about 16 years before impact. The authors note that such a deflection

maneuver is already achievable with currently existing technologies.

However, their study illustrates that things are not always that easy.

The other asteroid they considered, 2004 VD17, has an orbit closely

overlapping that of Earth's over a longer span than 99942 Apophis does,

and such orbital characteristics makes its deflection much more tricky.

Still, the scientists found windows of opportunity such as one in 2021,

81 years before its hypothesized collision with Earth, in which an

impactor weighing about a ton could deflect the asteroid away from

Earth.

The authors' findings also come with a bit of bad news.

While it may be technologically feasible to exert a force large enough

to deflect 2004 VD17, their calculations also reveal that the impactor

could shatter the asteroid, which is equivalent to converting an

approaching rifle bullet into a shotgun round, with consequences that

are unpredictable at best. 99942 Apophis, in contrast, should survive the relatively modest forces required to deflect it.

This study by Carusi et al. shows that deflecting real asteroids is

within reach of currently existing technologies, given enough time and

planning. By definition, NEAs orbit near Earth, so any that threaten us

are expected to have a few close encounters with Earth, during which

they are easy to find, before the final collision. Therefore, the long

planning period considered in this study is realistic.

The current study's strategy will not, however, work well

for deflecting objects with highly elliptical orbits such as long

period comets; nevertheless, most objects that impose

significant threats to Earth are NEAs since their orbits bring them so

close to here. The study highlights the importance of efforts such as

the SpaceWatch project hosted by the University of Arizona - its goal is to find and track all objects with chances of impacting Earth. It

may well turn out that spotting an asteroid heading our way before it

is too late is far more difficult than developing technologies to

deflect them.

American Chemical Society

Sun, 06 Apr 2008 11:19 EDT

Flash back three or four billion years - Earth is a hot, dry and

lifeless place. All is still. Without warning, a meteor slams into the

desert plains at over ten thousand miles per hour. With it, this

violent collision may have planted the chemical seeds of life on Earth.

Scientists presented evidence today that desert heat, a little

water, and meteorite impacts may have been enough to cook up one of the

first prerequisites for life: The dominance of "left-handed" amino

acids, the building blocks of life on this planet.

In a report at the 235th national meeting of the American Chemical

Society, Ronald Breslow, Ph.D., University Professor, Columbia

University, and former ACS President, described how our amino acid

signature came from outer space.

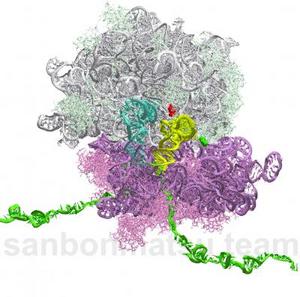

|

| ©Los Alamos National Laboratory |

| A simulated ribosome (white and purple subunits) processing an amino acid (green). |

Chains of amino acids make up the protein found in people, plants,

and all other forms of life on Earth. There are two orientations of

amino acids, left and right, which mirror each other in the same way

your hands do. This is known as "chirality." In order for life to

arise, proteins must contain only one chiral form of amino acids, left

or right, Breslow noted.

"If you mix up chirality, a protein's properties change enormously.

Life couldn't operate with just random mixtures of stuff," he said.

With the exception of a few right-handed amino acid-based bacteria,

left-handed "L-amino acids" dominate on earth. The Columbia University

chemistry professor said that amino acids delivered to Earth by

meteorite bombardments left us with those left-handed protein units.

"These meteorites were bringing in what I call the 'seeds of

chirality,'" stated Breslow. "If you have a universe that was just the

mirror image of the one we know about, then in fact, presumably it

would have right-handed amino acids. That's why I'm only half kidding

when I say there is a guy on the other side of the universe with his

heart on the right hand side."

These amino acids "seeds" formed in interstellar space, possibly on

asteroids as they careened through space. At the outset, they have

equal amounts of left and right-handed amino acids. But as these rocks

soar past neutron stars, their light rays trigger the selective

destruction of one form of amino acid. The stars emit circularly

polarized light - in one direction, its rays are polarized to the

right. 180 degrees in the other direction, the star emits

left-polarized light.

All earthbound meteors catch an excess of one of the two polarized

rays. Breslow said that previous experiments confirmed that circularly

polarized light selectively destroys one chiral form of amino acids

over the other. The end result is a five to ten percent excess of one

form, in this case, L-amino acids. Evidence of this left-handed excess

was found on the surfaces of these meteorites, which have crashed into

Earth even within the last hundred years, landing in Australia and

Tennessee.

Breslow simulated what occurred after the dust settled following a

meteor bombardment, when the amino acids on the meteor mixed with the

primordial soup. Under "credible prebiotic conditions" - desert-like

temperatures and a little bit of water - he exposed amino acid chemical

precursors to those amino acids found on meteorites.

Breslow and Columbia chemistry grad student Mindy Levine found that

these cosmic amino acids could directly transfer their chirality to

simple amino acids found in living things. Thus far, Breslow's team is

the first to demonstrate that this kind of handedness transfer is

possible under these conditions.

On the prebiotic Earth, this transfer left a slight excess of

left-handed amino acids, Breslow said. His next experiment replicated

the chemistry that led to the amplification and eventual dominance of

left-handed amino acids. He started with a five percent excess of one

form of amino acid in water and dissolved it.

Breslow found that the left and right-handed amino acids would bind

together as they crystallized from water. The left-right bound amino

acids left the solution as water evaporated, leaving behind increasing

amounts of the left-amino acid in solution. Eventually, the amino acid

in excess became ubiquitous as it was used selectively by living

organisms.

Other theories have been put forth to explain the dominance of

L-amino acids. One, for instance, suggests polarized light from neutron

stars traveled all the way to earth to "zap" right-handed amino acids

directly. "But the evidence that these materials are being formed out

there and brought to us on meteorites is overwhelming," said Breslow.

The steps afterward that led towards the genesis of life are

shrouded in mystery. Breslow hopes to shine more light on prebiotic

Earth as he turns his attention to nucleic acids, the chemical units of

DNA and its more primitive cousin RNA.

"This work is related to the probability that there is life

somewhere else," said Breslow. "Everything that is going on on Earth

occurred because the meteorites happened to land here. But they are

obviously landing in other places. If there is another planet that has

the water and all of the things that are needed for life, you should be

able to get the same process rolling."

Leonard David

Live Science

Fri, 04 Apr 2008 11:25 EDT

Keep an eye on a bill introduced in the House of Representatives by Congressman Dana Rohrabacher on Near Earth Objects (NEOs).

The NEO Preparedness Act calls upon the NASA Administrator to

establish an Office of Potentially Hazardous Near-Earth Object

Preparedness. That office would "prepare the United States for

readiness to avoid and to mitigate collisions with potentially

hazardous near-Earth objects in collaboration with other Agencies

through the identification of situation- and decision-analysis factors

and selection of procedures and systems."

NASA has also been tasked to request the National Academy of Science

to look into issues with detection of potentially hazardous NEOs and

approaches to mitigate these hazards. The exact statement of task is

still being hashed out, but that study should be underway in a couple

of months or so, I've been advised.

According to Jim Green, Director of NASA's Planetary Science

Division, speaking at a recent meeting on outer planet exploration,

part of the NEO assessment will focus on use of ground-based or

space-based observations for NEOs and approaches to developing

deflection capability.

It's not within NASA's charter to protect the planet from

threatening NEOs, Green noted. Such a mission could go to the

Department of Defense, he said, "but we'll see how it goes."

In NEO-related news, Green also reported on the huge Arecibo radio

telescope in Puerto Rico. "We have confirmed with the NSF [National

Science Foundation] that they will fully-fund Arecibo operations in

fiscal year 2008," he explained.

Conversation between NSF and NASA about funding Arecibo operations in upcoming years has begun, Green said.

Ananova

Mon, 07 Apr 2008 09:41 EDT

A Bosnian man whose home has been hit an incredible five times by meteorites believes he is being targeted by aliens.

Experts at Belgrade University have confirmed that all the rocks Radivoje Lajic has handed over were meteorites.

They are now investigating local magnetic fields to try and work out

what makes the property so attractive to the heavenly bodies.

But Mr Lajic, who has had a steel girder reinforced roof put on the

house he owns in the northern village of Gornja Lamovite, has an

alternative explanation.

He said: "I am obviously being targeted by extraterrestrials. I

don't know what I have done to annoy them but there is no other

explanation that makes sense. The chance of being hit by a meteorite is

so small that getting hit five times has to be deliberate."

The first meteorite fell on his house in November last year and

since then a further four have smashed into his home. The strikes

always happen when it is raining heavily, never when there are clear

skies.

He said: "I did not know what the strange-looking stones were at

first but I have since had them all confirmed as meteorites by experts

at Belgrade University.

"I am being targeted by aliens. They are playing games with me. I

don't know why they are doing this. When it rains I can't sleep for

worrying about another strike."

Patrick J. McDonnell and Andres D'Alessandro

Los Angeles Times/ LA Plaza

Mon, 07 Apr 2008 15:27 EDT

The space rock reportedly crashed late Sunday somewhere in Entre Rios Province, some 260 miles northwest of Buenos Aires, reports the daily Clarin,

which quoted a witness, Milton Blumhagen, a student and astronomy buff:

"For three or four seconds I saw an object in flames, changing color

until it turned blue when it approached the ground.'' A fire department

source said the impact was felt for miles around. No damage was

reported.

The curious are headed out to the isolated rural zone where the meteorite, or whatever it was, is believed to have struck.

Last year, as this L.A. Times news story recounts,

a meteorite strike near Lake Titicaca caused a regional sensation: Area

residents said they became sick, and meteor hunters rushed to the site

to purchase chunks of space debris, which can fetch high prices on the

international market. Scientists dismissed any links between the

meteorite and the reported illnesses.

Faye Flam

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Mon, 07 Apr 2008 09:09 EDT

Magnified 25,000 times under Drexel University's scanning electron

microscope, a couple of flecks of dirt offer up a landscape full of

crags, valleys, ridges - and, to Dee Breger's eyes, a window back in

time.

The tiny grains came from the sea floor below the Gulf of

Carpenteria in northern Australia, part of an underground layer dating

to the first millennium. Breger and her colleagues believe the material

holds signs that a fragment of a comet crashed to Earth during that

period. Such an event might explain the months of cold summers and dark

days that began in A.D. 536 and led to a well-documented period of

famine and unrest.

And, they say, while such an event would have been catastrophic, it

was not unique. By comparing the historical and archaeological records

with hard-to-prove physical evidence, they are trying to make a case

that rocks from space were responsible for altering human affairs in

ways so huge that some have entered mythology.

It is an uphill battle.

"We're mavericks," says Breger, a microscopist who is not formally

trained in science. Scanning her dirt sample on a nearby screen, she

zooms in on what looks like a splotch of paint. "We call that a splat."

Breger instructs the machine to analyze the composition. Traces of

some metals in the form of a splat can be a sign of a powerful

explosion, she says - one you might get if a piece of a comet or

asteroid slammed into the Earth.

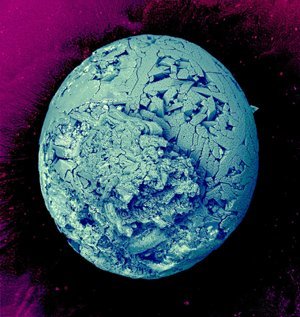

Scanning further, she stops at a sphere, less than a hundredth of a

millimeter across (much smaller than the width of a human hair). Under

the electron microscope it resembles a planet or some exotic moon, the

surface scarred with rifts and cracks, all suggestive of molten rock or

metal that was blasted into the air and quickly cooled.

It was Dallas Abbott, a marine geophysicist at Lamont-Doherty Earth

Observatory in New York, who brought these samples to Drexel. Breger

teamed up with Abbott while working at Lamont-Doherty, first as a

scientific illustrator and then as a microscopist. The former art

student moved to Drexel four years ago for the chance to work with more

powerful instruments.

"The lab here is state-of-the-art," she says.

They and a few colleagues in the Holocene Impact Working Group -

named for the period covering the last 20,000 years - have been

proposing for years that several large objects from space hit the Earth

with enough force to influence global climate within human history.

Abbott estimates this happened perhaps five times in the last 6,000

years.

Most sudden climate changes over the eons remain unexplained, and

most scientists argue that a lack of convincing evidence for any theory

is not much of a reason to support this one.

"Impacts are the solution of choice when you don't have any data,"

says astronomer Donald Yeomans of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Still, astronomers generally agree that the Earth has been smacked

around by comets and asteroids, and that some altered the history of

life. The most famous of them fell around 65 million years ago -

kicking up enough debris, it now appears, to cool the planet and kill

off the dinosaurs.

Much more recently, for 18 months around A.D. 536, a thick haze and

freakish cold gripped Europe. As Byzantine historian Procopius of

Caesarea put it: ". . . the sun gave forth its light without brightness

. . . and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams

it shed were not clear."

Tree growth rings dated to that time appear narrow and sickly as far

away as North America and Central Asia, an indication that the cold and

darkness spanned the globe. The period coincided with devastating crop

failures that some have linked to the fall of the Roman Empire.

There definitely was a climate anomaly at that time, says Richard

Alley, a climate expert and glaciologist at Penn State University. But

he, like most in the field, favors an alternative explanation: that a

large volcanic eruption dimmed the skies. Not only are eruptions

relatively common compared with large impacts, he says, there now

appears to be a record stored in ice caps near Greenland and Antarctica.

Scientists drilling out deep cores can date ice laid down in that

era to within a year or two, Alley says, and evidence of telltale

volcanic sulfates in layers from A.D. 536 was published just last month.

Looking more broadly, Abbott and Breger are also seeking clues to a

possible impact 4,800 years ago. Around that time, many different

cultures advanced myths of catastrophic floods, Abbott says, including

the biblical account of Noah's ark.

To find out what happened, she's gathering clues on scales small and

large. With satellite images now widely available through Google Earth,

Abbott is examining massive, V-shaped formations in northern Australia

and, at the other end of the Pacific, in Madagascar, the island off

East Africa. She argues that these were created by a giant impact in

the Indian Ocean that sent a mega tsunami in different directions.

"The one in Australia rises more than 100 feet above sea level,"

Abbott says. Her critics contend these are just big sand dunes created

by prevailing winds, an explanation that she says doesn't go nearly far

enough.

And the actual point of impact?

With remote sensing technology, Abbott says she's found signs that

might indicate the presence of an 18-mile-wide crater. But it's more

than 1,000 feet below the surface and hard to confirm. She's seeking

funding for a more thorough exploration.

If they put together enough lines of evidence for enough separate

events, Abbott says, the work may back up an idea promoted by a

minority of British astronomers that a few thousand years ago a massive

comet swung inward from the fringes of the solar system, broke up near

the Earth - and has been periodically dropping pieces on the planet

ever since.

What's left, these astronomers proposed, is now called Comet Encke -

a tiny chunk of ice and dirt that orbits the sun every three years.

Others say that while the idea that pieces of what is now Encke fall

to earth is plausible, the evidence is unconvincing. "It's a little

dinky comet right now," says David Morrison, a planetary scientist at

NASA's Ames Research Center in California. "If Encke was responsible

for something, it's aged quickly."

By tracking asteroids that cross Earth's orbit and observing craters

on the moon's surface, astronomers are able to estimate how frequently

they hit in the past. Potentially climate-changing impacts with

asteroids average less than once in a million years, they say, and

comet collisions even less often.

That doesn't mean there weren't recent major comet impacts, Morrison says. It's just very unlikely.

Proving that a given geological formation was caused by an impact is

not a simple matter even when it's on land, says Jay Melosh, a

planetary scientist at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary

Lab.

It's even harder under water. In that case, one of the best

indicators is the concentration of rare elements, especially iridium,

that would have come with the comet or asteroid and then blasted

through the atmosphere on impact.

And it's one thing to find evidence of an impact, Melosh says, and

another to demonstrate that it was big enough to lead to global climate

change.

The only clear-cut case is the impact that marked the end of the

dinosaur era 65 million years ago. Underwater remote sensing has found

a massive crater under the Gulf of Mexico, and geologists have

discovered more than 200 places around the globe where rock samples

have yielded unusually high levels of iridium in the same layer of

geological strata after which dinosaurs suddenly vanish.

Mainstream astronomers say asteroids and comets do hit often enough

that we should worry about them. Those optimistic enough to think we'll

survive more than a few thousand years say a rock or comet will

eventually get us. Unless we can figure out how to deflect it, we will

go the way of the dinosaurs.

Science Daily

Tue, 08 Apr 2008 11:58 EDT

The Indiana Asteroid Program began with a borrowed lens and a

bet over a chocolate ice cream cone. Almost 60 years later, its final

chapter was written with the naming of a heavenly body after one of the

most dedicated staff members Indiana University Bloomington's

Department of Astronomy has ever seen.

The program -- launched in 1949 by Hoosier astronomy legend Frank

Edmondson -- aimed to locate and calculate the orbits of asteroids

"lost" during World War II. During the next 28 years, the program also

identified 119 new asteroids by studying more than 3,500 image plates

showing 12,000 asteroid images.

But because asteroids are not named until their orbits are

calculated and confirmed, the final IU asteroid wasn't named until

earlier this year, more than 40 years after the program ceased

searching the skies.

Frank Edmondson, now professor emeritus of the Department of

Astronomy, headed the program when this last asteroid was discovered,

thus was responsible for its naming -- he named it in honor of Brenda

Records, who recently retired as office manager of the astronomy

department after 20 years of exemplary service.

"I did not expect it at all," said Records, who now spends her time

at home and visiting her grandchildren in Louisville. "I was very

surprised and honored that Frank named the asteroid after me."

Edmondson named the final IU asteroid, "Records," partly due to her

efforts as office manager and administrative assistant, and partly in

recognition of her hard work transcribing his book, AURA and its U.S. National Observatories.

Records -- one of the few people who could read Edmondson's handwriting

-- spent years typing his manuscript, which was written in longhand.

"Brenda was a very important part of the astronomy department for a

very long time and instrumental in getting my book published," said

Edmondson. "We were very lucky to have her."

During the Indiana Asteroid Program's tenure, Edmondson and company

discovered many asteroids and named them after Indiana astronomers and

faculty, both recent and retired. Some familiar names include IU

Presidents Bryan and Wells, IU astronomers K.P. Williams and Wilbur

Cogshall, current IU faculty members James Glazier and Stuart Mufson,

and famous Indiana astronaut Gus Grissom.

"There are some pretty major chunks of rocks -- some the size of

Bloomington -- floating around out there bearing the names of some very

famous IU faculty, staff and alumni," said IU Astronomy Professor

Emeritus R. Kent Honeycutt, who has served as chair of the astronomy

department twice and is currently director of the university's Goethe

Link Observatory.

Edmondson, now 95, began building the astronomy department with a

chocolate ice cream cone. In 1937, he bet Astronomy Department Chair

William Cogshall a chocolate ice cream cone that recently appointed IU

President Herman Wells would fund a graduate student fellowship

position at the newly constructed Goethe Link Observatory in Brooklyn,

Ind. At that time, the observatory belonged to Dr. Goethe Link, an

Indianapolis surgeon and amateur astronomer.

Cogshall doubted they would get the funding, but must have wanted

that chocolate ice cream cone, because he ultimately agreed. What he

didn't know was that Edmondson had already convinced Wells to fund the

position.

"You may question my morals," said Edmondson, grinning broadly. "But

I was betting on a sure thing, and the bet got the money to start the

program."

The position proved instrumental to both the Indiana Asteroid

Program and the astronomy department because a decade later, the

astronomer Edmondson hired -- James Cuffey -- located and borrowed a

10-inch lens from the University of Cincinnati to search for asteroids.

Without that lens, the Indiana Asteroid Program would have never

existed.

Edmondson and Cuffey decided to acquire the lens because the

International Astronomy Union had issued a plea for help to search for

asteroids with orbits that had been lost during the war due to

observatories shutting down.

"We felt it was our duty to help if we could," said Edmondson. "And

none of it would have happened without that 10-inch lens, Dr. Cuffey,

or that chocolate ice cream cone."

Ker Than

National Geographic

Thu, 10 Apr 2008 16:41 EDT

The meteorite that wiped out the dinosaurs might have been less than half the size of what previous models predicted.

That's the finding of a new technique being developed to estimate

the size of ancient impactors that left little or no remaining physical

evidence of themselves after they collided with Earth.

Scientists working on the technique used chemical signatures in

seawater and ocean sediments to study the dino-killing impact that

occurred at the end of the Cretaceous period, about 65 million years

ago.

They also looked at two impact events at the end of the Eocene epoch, roughly 33.9 million years ago.

In what could be a major scientific puzzle, the team's new size

estimate for the dino-killing meteorite is a mere 2.5 to 3.7 miles (4

to 6 kilometers) across.

The most recent computer models predicted a size of 9 to 12 miles (15 to 19 kilometers) across.

The team notes that their findings could also mean that the makeup

of the impactor is different from what scientists commonly assume.

"We are hoping this will lead to further work," said study leader Gregory Ravizza of the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

Impact Fingerprints

The fiery passage of asteroids and comets through Earth's atmosphere leaves chemical traces in the land, sea, and air.

The most common types of meteorites to hit Earth are chondrites, stony objects that originate in the asteroid belt.

Chondrites contain two different versions, or isotopes, of the naturally occurring element osmium: osmium 187 and osmium 188.

Seawater and sediments also contain the two osmium isotopes, but the

ratio of osmium 187 to osmium 188 is usually much larger in the ocean

than it is in chondrites.

When a small- to medium-size meteorite enters Earth's atmosphere,

much of the object is vaporized and the osmium ratio in seawater around

the world is temporarily decreased.

Over time, this osmium imprint is transferred to sediments at the ocean bottom, creating a more enduring record of the impact.

The new technique therefore looks for osmium spikes in ocean

sediments and analyzes the isotope ratio. Scientists can then predict

when an impact event occurred and the size of the projectile.

The research is detailed in tomorrow's issue of the journal Science.

Dramatic Upheaval

In addition to the smaller Cretaceous impact, the team estimates

that two known meteorites from the late Eocene were smaller than

previously believed.

Boris Ivanov, an impact modeler at the Russian Academy of Sciences,

said that if the new size estimates prove correct, they would create a

"dramatic controversy" within the impact physics community.

"Most numerical modeling specialists believe the current modeling

gives us fidelity of a factor of a few times the mass of a projectile

with assumed average impact velocity," Ivanov said.

Study co-author Francois Paquay, also at the University of Hawaii,

said that more work needs to be done to confirm the latest estimates.

"We think the discrepancy is important and it will need to be addressed in future [scientific] meetings," Paquay said.

Jay Melosh, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University who

was not involved in the study, called the new method a "potentially

powerful" technique for filling gaps in the geologic impact record.

"It's a very valuable contribution to the tool kit of ways we have

of estimating the presence of impacts in the geologic record," Melosh

said.

Astrobiology Magazine

Thu, 10 Mar 2005 18:26 EST

Scientists have discovered why there isn't much impact-melted rock

at Meteor Crater in northern Arizona.The iron meteorite that blasted

out Meteor Crater almost 50,000 years ago was traveling much slower

than has been assumed, University of Arizona Regents' Professor H. Jay

Melosh and Gareth Collins of the Imperial College London report in the

cover article of Nature.

"Meteor Crater was the first terrestrial crater identified as a

meteorite impact scar, and it's probably the most studied impact crater

on Earth," Melosh said. "We were astonished to discover something

entirely unexpected about how it formed."

|

| ©Jim Hurley |

| Meteor Crater, Arizona |

Previous

research supposed that the meteorite hit the surface at a velocity

between about 34,000 mph and 44,000 mph (15 km/sec and 20 km/sec).

The meteorite smashed into the Colorado Plateau 40 miles east of

where Flagstaff and 20 miles west of where Winslow have since been

built, excavating a pit 570 feet deep and 4,100 feet across enough room

for 20 football fields.

Melosh and Collins used their sophisticated mathematical models in

analyzing how the meteorite would have broken up and decelerated as it

plummeted down through the atmosphere.

About half of the original 300,000 ton, 130-foot-diameter

(40-meter-diameter) space rock would have fractured into pieces before

it hit the ground, Melosh said. The other half would have remained

intact and hit at about 26,800 mph (12 km/sec), he said.

That velocity is almost four times faster than NASA's experimental

X-43A scramjet -- the fastest aircraft flown -- and ten times faster

than a bullet fired from the highest-velocity rifle, a 0.220 Swift

cartridge rifle.

But it's too slow to have melted much of the white Coconino

formation in northern Arizona, solving a mystery that's stumped

researchers for years.

Scientists have tried to explain why there's not more melted rock at

the crater by theorizing that water in the target rocks vaporized on

impact, dispersing the melted rock into tiny droplets in the process.

Or they've theorized that carbonates in the target rock exploded,

vaporizing into carbon dioxide.

"If the consequences of atmospheric entry are properly taken into

account, there is no melt discrepancy at all," the authors wrote in Nature.

"Earth's atmosphere is an effective but selective screen that

prevents smaller meteoroids from hitting Earth's surface," Melosh said.

When a meteorite hits the atmosphere, the pressure is like hitting a

wall. Even strong iron meteorites, not just weaker stony meteorites,

are affected.

"Even though iron is very strong, the meteorite had probably been

cracked from collisions in space," Melosh said. "The weakened pieces

began to come apart and shower down from about eight-and-a-half miles

(14 km) high. And as they came apart, atmospheric drag slowed them

down, increasing the forces that crushed them so that they crumbled and

slowed more."

Melosh noted that mining engineer Daniel M. Barringer (1860-1929),

for whom Meteor Crater is named, mapped chunks of the iron space rock

weighing between a pound and a thousand pounds in a 6-mile-diameter

circle around the crater. Those treasures have long since been hauled

off and stashed in museums or private collections. But Melosh has a

copy of the obscure paper and map that Barringer presented to the

National Academy of Sciences in 1909.

At about 3 miles (5 km) altitude, most of the mass of the meteorite

was spread in a pancake shaped debris cloud roughly 650 feet (200

meters) across.

The fragments released a total 6.5 megatons of energy between 9

miles (15 km) altitude and the surface, Melosh said, most of it in an

airblast near the surface, much like the tree-flattening airblast

created by a meteorite at Tunguska, Siberia, in 1908.

The intact half of the Meteor Crater meteorite exploded with at

least 2.5 megatons of energy on impact, or the equivalent of 2.5 tons

of TNT.

Elisabetta Pierazzo and Natasha Artemieva of the Planetary Science

Institute in Tucson, Ariz., have independently modeled the Meteor

Crater impact using Artemieva's Separated Fragment model. They find

impact velocities similar to that which Melosh and Collins propose.

Melosh and Collins began analyzing the Meteor Crater impact after

running the numbers in their Web-based "impact effects" calculator, an

online program they developed for the general public. The program tells

users how an asteroid or comet collision will affect a particular

location on Earth by calculating several environmental consequences of

the impact. The program is online.

David Shiga

NewScientist

Thu, 10 Apr 2008 19:11 EDT

|

| ©CDW/NSF |

| Most asteroid impacts on Earth have left few persistent signs, but they may still be detectable in ocean sediment records. |

Mud at the bottom of the ocean holds precious clues about asteroids that struck Earth in the past, a new study reveals.

Scientists would love to have a better record of asteroid and comet

impacts to understand how these catastrophic events have affected life

and Earth's climate. But most impactors that made it through the

atmosphere either gouged out a crater that was subsequently erased or

splashed into the ocean.

Now, scientists have developed a new tool to uncover these events,

based on concentrations of the metal osmium found in mud at the bottom

of the ocean. The technique was developed by François Paquay of the

University of Hawaii in Honolulu, US, and his colleagues.

Osmium atoms come in several varieties, or isotopes. Paquay's team

looked at two particular isotopes, one of which is slightly heavier

than the other. Crucially, the osmium in meteorites is much richer in

the lighter form than the stuff native to Earth. As a result,

scientists can determine how much of the otherworldly stuff is present

in any given deposit of the metal they find.

Paquay's team has been looking for the metal in samples of ocean

sediment obtained by drilling into the ocean floor. The sediment was

laid down in layers over time, allowing scientists to date when they

were deposited.

Multiple strikes

In 1995, members of Paquay's team pointed out high levels of the

lighter osmium isotope - associated with extraterrestrial material - in

ocean sediment laid down around the time of the impact that killed off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Since then, they have found another big spike in extraterrestrial

osmium laid down at the time of another known impact event that

happened 35 million years ago. At that time, multiple impacts shook the

Earth in what is known as the Late Eocene impacts.

The team estimates that 80,000 tonnes of osmium from the object that

wiped out the dinosaurs was vaporised by the heat of the impact. It

then dissolved into seawater and eventually accumulated on the ocean

floor. The Late Eocene impacts 35 million years ago laid down an

estimated 20,000 tonnes.

Smaller impacts

Based on these amounts, the team estimates that the dinosaur-killing

object was 4.1 to 4.4 kilometres across, while the largest of the Late

Eocene impactors would have been 2.8 to 3 km across.

These are much lower than previous estimates based on the size of

the craters associated with these events. These have given impactor

size estimates of 15 to 19 km for the one that killed off the

dinosaurs, and 8 km for the larger of two impactors involved in the

Late Eocene impacts.

What accounts for the difference? For one thing, the calculations by

Paquay's team assume that 100% of the osmium from the impactors was

vaporised and dissolved into seawater. If a smaller percentage actually

ended up on the ocean floor, then the impactors could have been bigger.

Comet impacts?

But even after taking this into account, Paquay thinks the impactors

were smaller than the crater-based calculations suggest. If the

impactors were as large as these calculations imply, then 90% of the

osmium from the impactors is hiding somewhere other than in ocean

sediment. "We think that this is unlikely, but we can't rule this

possibility out without additional work," he says.

Another possibility is that the impacting objects were comets rather

than asteroids, and contained much less osmium to begin with. But

chemical traces of the impactors left behind in rocks and reported in

previous studies suggest otherwise.

Kenneth Farley of Caltech in Pasadena, US, who has studied other traces of impacts in sediment, but is not a member of Paquay's team, is impressed with the new method.

"I am hoping that this technique will allow the detection of

previously unknown impacts so we can get a better handle on impact

frequency and assess whether - and how - impacts affect life and

climate," he told New Scientist.

Unique signature

Although impacts are also known to contribute unusually large

amounts of an element called iridium to sediment, the iridium

concentrations are much harder to translate into impactor sizes, Farley

says.

Unlike osmium, extraterrestrial iridium does not have a unique

isotope signature, so is harder to distinguish from iridium native to

Earth.

And while samples show osmium is laid down evenly across the planet,

the distribution of iridium is very patchy, making it hard to draw

conclusions without a large number of samples from different parts of

the planet.

Journal reference: Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.1152860)

Comets and Asteroids - Learn more about the threat to human civilisation in our special report.

Comment: Read our Special Report series: Comets and Catastrophe

NSF

Fri, 11 Apr 2008 17:14 EDT

Scientists have developed a new way of determining the size and frequency of meteorites that have collided with Earth.

Their work shows that the size of the meteorite that likely

plummeted to Earth at the time of the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T)

boundary 65 million years ago was four to six kilometers in diameter.

The meteorite was the trigger, scientists believe, for the mass

extinction of dinosaurs and other life forms.

François Paquay, a geologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa

(UHM), used variations (isotopes) of the rare element osmium in

sediments at the ocean bottom to estimate the size of these meteorites.

The results are published in this week's issue of the journal Science.

When meteorites collide with Earth, they carry a different osmium

isotope ratio than the levels normally seen throughout the oceans.

"The vaporization of meteorites carries a pulse of this rare element

into the area where they landed," says Rodey Batiza of the National

Science Foundation (NSF)'s Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the

research along with NSF's Division of Earth Sciences. "The osmium mixes

throughout the ocean quickly. Records of these impact-induced changes

in ocean chemistry are then preserved in deep-sea sediments."

Paquay analyzed samples from two sites, Ocean Drilling Program (ODP)

site 1219 (located in the Equatorial Pacific), and ODP site 1090

(located off of the tip of South Africa) and measured osmium isotope

levels during the late Eocene period, a time during which large

meteorite impacts are known to have occurred.

"The record in marine sediments allowed us to discover how osmium changes in the ocean during and after an impact," says Paquay.

The scientists expect that this new approach to estimating impact

size will become an important complement to a more well-known method

based on iridium.

Paquay, along with co-author Gregory Ravizza of UHM and

collaborators Tarun Dalai from the Indian Institute of Technology and

Bernhard Peucker-Ehrenbrink from the Woods Hole Oceanographic

Institution, also used this method to make estimates of impact size at

the K-T boundary.

Even though these method works well for the K-T impact, it would

break down for an event larger than that: the meteorite contribution of

osmium to the oceans would overwhelm existing levels of the element,

researchers believe, making it impossible to sort out the osmium's

origin.

Under the assumption that all the osmium carried by meteorites is

dissolved in seawater, the geologists were able to use their method to

estimate the size of the K-T meteorite as four to six kilometers in

diameter.

The potential for recognizing previously unknown impacts is an important outcome of this research, the scientists say.

"We know there were two big impacts, and can now give an

interpretation of how the oceans behaved during these impacts," says

Paquay. "Now we can look at other impact events, both large and small."

The London Telegraph

Sat, 12 Apr 2008 07:54 EDT

A Bosnian man claims his home has been hit five times by meteorites.

Radivoje Lajic claims he is being targeted by aliens and has reinforced his roof in Gornja Lamovite with a steel girder.

He said: "I am obviously being targeted by aliens. I don't know

what I have done to annoy them but there is no other explanation that

makes sense.

"The chance of being hit by a meteorite is so small that getting hit five times has to be deliberate."

The chances of just one meteor hitting your house is many billions to one.

Belgrade University has confirmed that all the rocks Mr Lajic has

handed over were meteorites, but not that they all hit his house.

An investigation is under way into local magnetic fields to see if they have any influence.

The first meteorite fell on Mr Lajic's house in November and since then a further four have smashed into his home, he claims.

The strikes happen when it rains, he said.

"I don't know why they are doing this. When it rains I can't sleep for worrying about another strike."

Lisa Duchene

PsyOrg

Wed, 09 Apr 2008 14:57 EDT

In the early morning darkness on April 15, 1912, as the R.M.S.

Titanic was sinking in the freezing Atlantic, survivors witnessed a

large number of streaking lights in the sky, which many believed to be

the souls of their drowning loved ones passing to heaven.

|

| ©Yan On-Sheung |

Says Kevin Luhman, what they most likely were seeing was the peak